What is Long Past Occurs in Full Light is Marilyn Bowering’s new book of poetry from Mother Tongue Publishing. It was summertime and the livin’ was easy as the song says so I sat down to read the book as soon as it arrived in my mailbox. What a special treat that was!

What is Long Past Occurs in Full Light is Marilyn Bowering’s new book of poetry from Mother Tongue Publishing. It was summertime and the livin’ was easy as the song says so I sat down to read the book as soon as it arrived in my mailbox. What a special treat that was!

Marilyn is a poet, novelist and librettist who lives in Victoria. I first met Marilyn in 1996 in Toronto when she did a reading at Tallulah’s Cabaret at Buddies in Bad Times Theatre. Because I’m such a keen archivist, I have the clipping of the reading tucked in her book, Autobiography, so I know the exact date: November 12th at 7:30 p.m. The other readers were Daphne Marlatt and Cordelia Strube.

My copy of Autobiography, published by Beach Holme Publishers, has an inscription from Marilyn with “best wishes for mirror gazing.” I have seen Marilyn on Vancouver Island since then but I remember that first meeting and our talk of “mirror gazing” which is the title of one of her poems and a section of the book. (Mirror gazing is a way to bridge our world to the spirit realm where we may connect with dead ancestors.)

I did not ask the dead to come,

they came anyway,

The uncles, fat as sea-lions,

the aunts, patting waved hair.

…

From “Mirror Gazing (for Pepe)” by Marilyn Bowering

I’m still fascinated by the concept which could apply to the life writing we do when our ancestors may appear, unbidden.

Poets do embellish and imagine in reaching for a magical metaphor. However, real life experiences can be stranger, as they say, than fiction.

In her poem, “After,” in her new book, Marilyn writes:

Sunlight opens a path

beneath the ironing board;

the clock remains on the counter.

The door swings open,

and the milk bottles on the porch

prepare themselves.

In the mud of retreating water,

at the bottom of the steps,

a wedding dress irons itself smooth

on wet stones.

I love the everyday details of the ironing board and the animated milk bottles. And what could have happened to the poor bride whose dress is ironing itself smooth on wet stones?

A beautiful addition to What is Long Past Occurs in Full Light is Marilyn’s section of Notes in the back so we learn some history about the haunting poem “After.” Marilyn was told by her mother that “her wedding dress had been lost in the flooding of our house by the Seine River, a tributary of the Red River, near which we lived when I was a year old. I have glimmers of recollection: a canoe at the back door; the fridge tied to the stairs; and lights reflecting off the water, nearly at bridge deck level, as we journeyed to safety when evacuated one night.”

As terrifying as the flood would have been, the domestic images are strange and wonderful. The fridge tied to the stairs!

The first of the three sections in which the poem noted above is included, is titled “Missing” for a poem of the same name. “Missing” begins with an epigraph by George Seferis: “I’ve acquired the habit of murmuring aloud the names of cities that have sunk of out sight.”

The poem names three Haida villages “that have sunk out of sight: Naikun, Hiellan, Gahlinskun.” They were located on Graham Island, Haida Gwaii, B.C. where Marilyn was a schoolteacher for a time, specifically in Massett (these days spelled “Masset”).

The last stanza begins:

“If memory has neither beginning nor end,” one of us says,

and she steps out from the dunes

and snaps the threads of concealment.

The word “concealment” resonates with me as I’m reading a a book by Haida artist, performer, and activist Terri-Lynn Williams-Davidson: Out of Concealment (Heritage House, 2017). The book is Terri-Lynn’s reimagining of the ancient Supernatural Beings of Haida Gwaii which she says are “epic figures in the Haida Nation’s origin stories, which have been passed down for millennia.”

We reimagine villages too as we learn the names of them and listen to the stories handed down about the villages that once thrived before European contact. One of the voices in the poem says “If memory has neither beginning nor end,” an enduring concept.

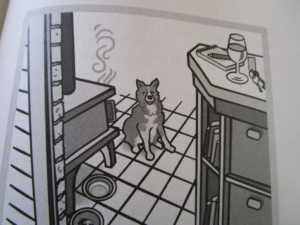

“Woof – at the Door – Woof” is the second section of the book with sixteen poems accompanied by illustrations by Ken Laidlaw. In an afterword to the section, Marilyn explains that her “vivid and gentle sixteen-year-old border collie, Tessa” died as she was in the midst of packing to leave the house in Sooke where she had lived for thirty-five years.

“Woof – at the Door – Woof” is the second section of the book with sixteen poems accompanied by illustrations by Ken Laidlaw. In an afterword to the section, Marilyn explains that her “vivid and gentle sixteen-year-old border collie, Tessa” died as she was in the midst of packing to leave the house in Sooke where she had lived for thirty-five years.

“The Writers’ Museum” is the title of the third section of the book and a poem by the same name dedicated to the late Stephen Reid (1950 -2018). The Writers’ Museum is in Edinburgh where there are objects that belonged to Robert Louis Stevenson, Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott. Marilyn finds it a place of peace and thinks her friend Stephen “might have found peace, too. These writers knew suffering when they were children, each struggled during tumultuous times, and yet each created beautiful literary works.”

In the poem, Marilyn imagines on behalf of her friend and refers in the poem to “this letter of grief.”

Imagine a door in the writers’ museum

through which everything lost

is recovered.

The title of Marilyn’s book, What Is Long Past Occurs in Full Light, is from the poem “The Master” by Czeslaw Milosz and is a phrase that acts as an epigraph to “Out of the Shadows,” in the third section of the book.

There are many references to light such as in “Wild” which begins with an epigraph by Robert Bringhurst and ends with:

Nothing is finished, you are here with me:

we have only drifted to earth by its light

to open the soil.

It’s a lovely poem in which the narrator works in the garden to

“let its waves decide the hour.”

The poem “Epiphany” refers to the twelve days after the birth of the Christ Child “when three Wise Men are said to have brought gifts for him,” Marilyn says in her notes. King Herod, fearing the child “would be a threat to his power . . . ordered the murder of all male children under the age of two in the region of Bethlehem. This is known as the Massacre of the Innocents.”

The family of three escaped according to the Biblical story and in the poem, the dogs

led Joseph and Mary,

when they shouldered their world-sacks,

past killers in convoys,

in bombed-out cities

so a child might open a new page of light

and drive evil away.

Let them in. Let them in.

In the final poem, “Basho,” the poet refers to the “most famous poet of the Edo period in Japan born in 1694 as well as to Plato to whom “the question of truth in poetry was significant” yet “thought its achievement rarely possible.” From the poem:

We should ban the poets, yes, if they want to tell more

than how light falls on a face last thing at night,

or when they won’t confirm the colour of a passing woman’s coat –

. . .

Jan Zwicky describes Marilyn Bowering as “one of our essential poets.” In a cover endorsement, Jan says: “Despite her unflinching acknowledgement of the horrors humans visit on themselves and others, her vision is grounded in the subtle integrity of love.”

Marilyn writes of the natural world, locations and landscapes around the world, memories of home and family, and always weaves in the honouring of other poets. (I love “Catching Fire” with its references to Robin Skelton and Theodore Roethke’s shirts.) In all of the honouring Marilyn does in her poems, ordinary moments, current and long past, become extraordinary and exquisite with the full light of this particular poet focused on them.

As part of the Nanaimo Poet Laureate reading series, Marilyn Bowering will be reading along with Joanna Streetly on Saturday, November 16 at 1 p.m. at the Harbourfront branch of the Vancouver Island Regional Library in Nanaimo. Joanna’s latest book of essays is Wild Fierce Life: Dangerous Moments on the Outer Coast (Caitlin Press, 2018).

What a great review Mary Ann. Should be a fine reading.