Jess Housty (Cúagilákv) photo by Rhon Wilson

I first “met” Jess Housty (Cúagilákv) in the pages of This Place is Who We Are by Katherine Palmer Gordon published by Harbour Publishing in 2023. Jess was one of the Heiltsuk (Haíɫzaqv) community members featured in a chapter entitled “Haíɫzaqv Unfettered” about the community of Wágḷísḷa (Bella Bella, British Columbia) on unceded ancestral territory where the Heiltsuk people have lived for at least fourteen thousand years. Haíɫzaqv citizens devoted many years to protest campaigns and eventually defeated Enbridge Inc.’s proposed Northern Gateway pipeline.

At the time of publication, Jess was the executive director of the Qqs Projects Society, a Haíɫzaqv charitable non-profit organization supporting youth and families. As well as being an active community volunteer, and parent to two young boys, Jess was endeavoring to immerse them in their language and cultural traditions.

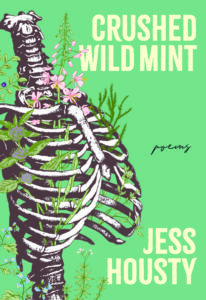

Jess has a reverence for the land, ancestors, traditions, and the language of the Heiltsuk people as evidenced in their gorgeous first book of poetry, Crushed Wild Mint, published by Nightwood Editions (2023). As Eden Robinson says in her endorsement: “When the mountains of your territory are your ancestors, you paint the landscapes as Jess Hosuty does” and “Housty’s hyperlocality is precise medicine.”

Jess’s bio says they are “a parent, writer and grassroots activist with Heiltsuk and mixed settler ancestry. They serve their community as an herbalist and land-based educator alongside broader work in the non-profit and philanthropic sectors.”

Prayer and praying are noted in several of the poems in Crushed Wild Mint, particularly in the first two sections of the book.

In their first poem, The Future, the poet writes:

We each deserve to settle into the ease

of ceremony, to nestle

amongst our grandmothers’ skirts

and spill love back into our bodies.

Praying is dreaming out loud

with my ancestors.

Praying is giving a voice and anatomy

to futurity.

The lines of Nearshore Prayer say:

This is a prayer that extends

in the direction of the ocean:

It is not a story; nothing

is apocryphal in prayer.

The poems are exquisite in their simplicity, with textural details, and quietly powerful. Jess is an herbalist, as mentioned, and their noting of “wild rose petals, your field mint, / the sweet, deep sting of your nettles” offers a sensory description as if the scent wafts off the page. (Ruminant / Remnant)

The poems are exquisite in their simplicity, with textural details, and quietly powerful. Jess is an herbalist, as mentioned, and their noting of “wild rose petals, your field mint, / the sweet, deep sting of your nettles” offers a sensory description as if the scent wafts off the page. (Ruminant / Remnant)

When a Heiltsuk word is used as a poem’s title it’s as if the poem becomes a story of that word. With the poem Máɫuala for instance, readers are asked: “Who taught you to pray?” The poem offers some contemplation on the subject of prayer which the poet describes as:

Less palm to palm

and more palm to water,

sole to shore, brow to sun,

brow to rain.

The English translation of máɫuala is “two people walking together.”

In a poem To the scientist who called my beloved salmonberries ‘insipid’, the poet says:

I reclaim them now, and I ask their forgiveness:

they are my kin and they are rich.

Gwani (granny) or ǧáǧṃ́ (grandmother) is honoured in some of the poems. The first lines of Gwani Taught Me, are:

That every berry in my basket

is one syllable of a prayer.

The “simple authority of crushed mint” is noted in the poem Wilderness and in the title poem, Crushed Wild Mint, the poet shares their wisdom on dealing with Grief.

Crush wild mint

and put it in your pockets, in your hair,

in a bowl on the table.

Let the scent

cleanse Grief like smoke,

like cedar, like tenderness.

The rib cage as illustrated on the book’s cover designed by Angela Yen, is referred to in a poem entitled Remembering the Flood as a possible future shelter for “needlefish and rock crabs.”

Soon after Sarah and I moved to Nanaimo on Vancouver Island, Pauline Waterfall (also featured in the “Haíɫzaqv Unfettered” chapter noted above), invited me to facilitate a women’s writing circle in Bella Bella. I invited a friend from Toronto to join me so that we could add some movement and breathwork to the circle. One of the participants, due to the recalling of stories and music, was grateful to walk with her ancestors. My friend Ann-Marie and I were grateful for our time in the Heiltsuk community and honoured to be invited.

Jess Housty’s poetry celebrates all kin whether “a mouthful of soil from the / motherland” ( Ǧáǧṃ́ (II) ) or “sweet raven cracking me open” (Banquet). Their poems are intricately and exquisitely crafted.

As Jess says in their poem Instructions for Climbing Q̓aǧṃi (Mount Keyes): “The medicine shows the way.”

Will buy her book! Thank you M-A!

Sounds like a wonderful experience to engage with such a lovely book. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks Mary Ann for sharing these poems. They are delightful, so uncluttered, so meaningful.

OOh! I read your review with reverence, Mary Ann. It was clear to me that the messages in this poet’s writing were important, and precious.

Who taught me to pray, indeed? Neither parent, nor a granny. Parents were too busy making ends meet as was my grandmother (immigrant family struggles). I think it was Creator themselves who taught me. I am grateful.

And berries as syllables of a prayer – my spirit delighted in that phrase. Of course! it said to me. Every morsel is a syllable of a prayer of gratitude for sustenance, and for life itself.

Your review has stirred up some powerful emotions and thoughts and for that, I am grateful to you, Mary Ann. Namaste, Stephanie.

So glad to hear your spirit was delighted and powerful emotions were stirred for some future tending. Thank you Stephanie!