A poet friend posted a Calvin & Hobbs quote on Facebook: “There’s never enough time to do all the nothing you want.” That fit in with what I’ve been thinking about lately: Doing nothing is essential to the creative life.

In a book I’m reading, Clutter Intervention by Tisha Morris (Llewellyn Publications, 2018), the author says: “In art, empty space is called the negative space. In music, it’s the pause just prior to a crescendo. In homes, it’s the area where the space breathes. In meditation, it’s the pause between the inhale and exhale. In Japanese art (one of the few cultures that value empty space), the void is called ma and is highly regarded. In all art forms, the beauty lies in the empty space.”

I can definitely relate to what Tisha says about hanging on to unused art supplies and “inspiration files” of clippings that actually stagnate the creative process. “If it hasn’t given you inspiration yet, then it probably won’t,” Tisha says. “Inspiration happens in a flash, in peak moments of life, not in piles from yesteryear.” And inspiration happens when doing nothing.

Besides those pauses to which Tisha refers and the space I hope to create by letting things go, the space created by doing nothing is essential to one’s spiritual life. Zen Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh answered a child’s question, “Is nothing something?” with this answer: “Yes. Nothing is something. You have an idea in your head of nothing. You have an idea in your head of something. Both are things that can create either suffering or happiness. Nothing really is something.”

I wrote a poem quite a long time ago that I called “Fishing for Mermaids, Mining for Light.” I was inspired by a lunch I had with a friend, Arandi, in Guelph, Ontario. He and his wife Stella had moved to Guelph from Brazil so she could work on her Ph.D. at the University of Guelph. I met Arandi, a physicist, when he attended my creative writing class.

Here’s the poem:

Fishing for Mermaids, Mining for Light

At the corner of our cafe table,

between our neighbour’s steaming soup

and our quesadillas,

our conversation of poets and the like,

Neruda appears,

solid, like homemade bread, pan integral.

Neruda, the Chilean poet,

who descended into mines

to read poetry to workers

underground,

spent his Nobel prize money

on mermaids and shells,

wrote odes to honour

ordinary things.

We talk, as poets, of time we spend

listening,

when pen does not breathe on paper,

our observations stored in pitchy cupboards

to be obliged when they are ready.

Rarely see the server,

that seems to be okay.

The quesadillas are tasty,

Neruda is near,

as we bemoan the days

when nothing seems to happen.

There’s a lot of something when nothing seems to happen – lunch with a friend, the writing life, sightings of Pablo Neruda, inspiration to write a poem.

My intent for the month of July this summer was to do nothing. I did do things but figured I’d just go with the flow, do things when I felt the energy for them. I wanted the sort of “cottage time” Sarah and I have enjoyed in the past when we rented a cottage on Lake Huron in Ontario. We still “accomplished” things but there was such an easy flow to everything we did. We loved sitting at the table in front of the window in the morning and following breakfast, continuing to read and write. We’d eventually meander down to the water for a walk and again in the evening to see the sunset. Other vacations are quite different if you’re in a new area and really want to use the time to see all there is to see but in that cottage on Lake Huron there was nothing we had to do and nowhere we had to go.

That reminds me of a Joseph Campbell quote about having a “bliss station” (The Power of Myth by Joseph Campbell with Bill Moyers, Doubleday, 1988): You must have a room, or a certain hour or so a day, where you don’t know what was in the newspapers that morning, you don’t know who your friends are, you don’t know what you owe anybody, you don’t know what anybody owes to you. This is a place where you can simply experience and bring forth what you are and what you might be. This is the place of creative incubation. At first you may find that nothing happens there. But if you have a sacred place and use it, something eventually will happen.

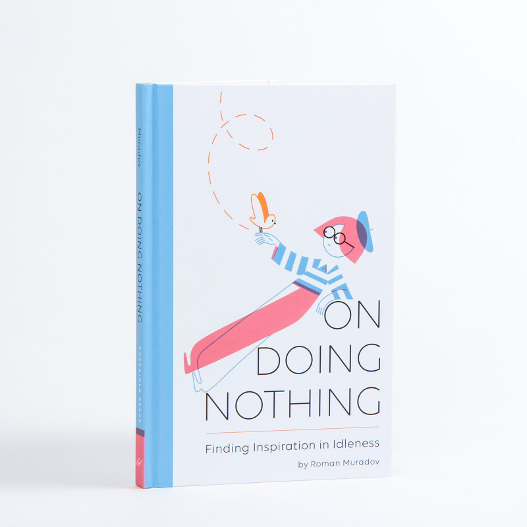

I was curious about a book entitled On Doing Nothing: Finding Inspiration in Idleness by Roman Muradov (Chronicle, 2018) as idleness is my favourite thing to do or not do as the case may be. The book is a delightful one with illustrations by the author who is originally from Russia and now lives in San Francisco where he is a professor at California College of the Arts. According to his bio, “he has a penchant for long, aimless walks and an imaginary dog named Barchibald.” An imaginary dog, I like that. Better for getting outside than an imaginary walk.

There’s a difference in not doing anything and doing nothing Muradov says. “The difference is in the act: unlike plain indolence, doing nothing is a considered attitude that calls at once for patience and alertness.”

“We don’t need to do much to cultivate idle thought,” Muradov writes. “All it takes is to attune our minds to subtler movements, recognizing their arrivals and translating them into the medium of choice, whether it’s a walk in the park or an hour of painting.”

“We don’t need to do much to cultivate idle thought,” Muradov writes. “All it takes is to attune our minds to subtler movements, recognizing their arrivals and translating them into the medium of choice, whether it’s a walk in the park or an hour of painting.”

Most people are apt to fill their time with busyness. “There is no reason to do nothing,” Muradov says. “But then there is no reason to fall in love, or gather autumn leaves. Life reveals itself most fulsomely in gaps and intermissions.”

I was experiencing an “intermission” from my usual life while in Victoria for five weeks of radiation treatments in the late summer of 2015. I loved walking in various neighbourhoods of the city, observing so many details and objects that I often took photos of. Perhaps I was like the flaneur, from the French flaner – stroll, wander, drift. Charles Baudelaire defined the flaneur as the “passionate spectator.”

As Muradov points out in On Doing Nothing, “Like a private detective investigating the city for the pleasure of the investigation, the flaneur approaches the walk as both the process and the destination. It’s not necessarily a search for material; any ideas that may emerge, great or small, are secondary to the walk itself.

It was and can still be unsafe for women to walk alone. Lauren Elkin writes about that in Flaneuse: Women Walk the City in Paris, New York, Tokyo, Venice and London (Chatto & Windus, 2016). Jean Rhys is one of the women Lauren writes about.

“I passed a stationer’s shop where quill pens were displayed in the window,” Jean Rhys wrote. She thought some of them “would be all right in a glass to cheer up my table.” She bought about a dozen of them plus some black exercise books, “a box of J nibs, the sort I liked, an ordinary penholder, a bottle of ink and a cheap ink-stand. Now that old table won’t look so bare, I thought.”

“I passed a stationer’s shop where quill pens were displayed in the window,” Jean Rhys wrote. She thought some of them “would be all right in a glass to cheer up my table.” She bought about a dozen of them plus some black exercise books, “a box of J nibs, the sort I liked, an ordinary penholder, a bottle of ink and a cheap ink-stand. Now that old table won’t look so bare, I thought.”

The author, Lauren Elkin says: “This crucial step towards writing, came from wandering, from a need to cheer up an ugly table, to make a room her own.”

You don’t have to travel far to explore a new city or your own for that matter. You don’t even need to leave home to see the world as Franz Kafka wrote. Roman Muradov quotes him in On Doing Nothing: “Remain sitting at your table and listen. Do not even listen, simply wait. Do not even wait, be quiet, still and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked, it has no choice, it will roll in ecstasy at your feet.”

When it comes to making art, Muradov says: “The art of not making art is just as valuable as the act of making art. Delay can inform the work that is to come, or give existing work a different meaning.”

Nanaimo author, Carol Matthews, found that the delay in the publication of her book, Minerva’s Owl: The Bereavement Stage of My Marriage (Oolican Books 2017), helped her to realize another stage in the grieving of her husband’s death.

Nanaimo author, Carol Matthews, found that the delay in the publication of her book, Minerva’s Owl: The Bereavement Stage of My Marriage (Oolican Books 2017), helped her to realize another stage in the grieving of her husband’s death.

Carol told me: “While I was very frustrated by the delay it was that interim time, the waiting period, that allowed me to experience and write about the change that had taken place. I thought the book was complete with five sections ending with ‘Cleaving,’ but I think it’s a better book because ‘the in-between time’ allowed me to write ‘Surviving.’ “

Delays can be one of those times we are doing nothing along with being in grocery line-ups, corridors, buses, trains, airports, airplanes or elevators. They are places of in between, “fit for doing nothing.”

A few weeks ago, Sarah and I waited for our flight to Masset on Haida Gwaii, doing nothing in the south terminal of the Vancouver airport. And while on the plane itself and for the extra 45 minutes the plane circled until it could descend through a foggy patch, we were doing nothing. Haida Gwaii itself is known as the islands on the boundary between worlds so an ideal place for being idle, or just being.

“A delay allows us a better appreciation of our practice,” Muradov writes,”and a better understanding of our surroundings. It’s also a good way of learning patience.” He mentions “the willingness to put the tools aside, instead of stubbornly persisting onward” in the pursuit of art in any form. My partner Sarah Clark finds that to be the case. If she doesn’t know the next step in painting one of her mandalas, she leaves it for a time and moves on to something else.

Sarah created my mermaid “logo” while she was staying at a cottage on Lake Huron on her own. It was one of those in-between times not having to complete a task by a particular deadline, just following wherever her whims took her. The result was a whimsical drawing of a mermaid I call Moira Oenia who says: “Embrace Your Creative Self.”

Sarah created my mermaid “logo” while she was staying at a cottage on Lake Huron on her own. It was one of those in-between times not having to complete a task by a particular deadline, just following wherever her whims took her. The result was a whimsical drawing of a mermaid I call Moira Oenia who says: “Embrace Your Creative Self.”

“The most repetitive daily ritual can be a source of inspiration, if we examine it up close, and note the shifts and deviations.” That’s where the poetry comes in I would say. And a poem is made up of more than the printed words, “it’s also the spaces between the lines,” as Muradov points out.

Think of peeling an artichoke which Muradov describes in the section on “Repetition, Delay, Repetition.” It’s “an edible metaphor for any creative process,” he says. “The journey to its heart is an unhurried and repetitive sampling of minor delights and bitter disappointments. At the end, we’re left with a pile of discarded leaves as large as the fully-clothed thistle, if not larger.”

Slowing down, appreciating delays, doing nothing doesn’t usually describe people these days. In Madness, Rack, and Honey (Wave Books, 2012), Mary Ruefle writes that “the wasting of time is the most personal, most private, most intimate form of conversation with oneself, as well as another.”

I thought it was an interior decorator but apparently, according to Muradov, Mary Ruefle is the person who proposes arranging books by the colour of their spines – an active artistic exercise as well as “to escape the trappings of genre definitions.”

I thought it was an interior decorator but apparently, according to Muradov, Mary Ruefle is the person who proposes arranging books by the colour of their spines – an active artistic exercise as well as “to escape the trappings of genre definitions.”

Muradov says: “We can see art as a by-product of living, or we can treat our lives as works of art. How we define these margins is how we choose to spend our days, in steady rhythms, languid progressions, or improvised discord.”

Doing nothing can reinforce good working habits he says. “Most of [On Doing Nothing] was written on scraps of paper, on napkins, and occasionally on parts of the author’s anatomy. As the notes were deciphered, rewritten, and rewritten again (and again), they arranged themselves by theme into a fitting order. Although it took a while, the author never troubled himself with all-nighters or excess caffeine.” He rarely wrote or drew for more than a couple of consecutive hours and worked on the book every other morning. “Approaching a large project in small doses allows plenty of time for structural and conceptual links to pop up on their own, instead of being forced out of the brain with rusty garden pliers.”

“Active though is only one part of the artistic process, and for many artists it’s a proportionally small part. The rest happens during downtime, when the mind appears to be at rest, weaving invisible connections.”

Oh, I absolutely love it… wonderful quotes. Brilliant, soft insights. Such a leisurely meander through the fields of no-thing-ness. Thank you, thank you… and I’ll be sharing this on facebook!

Thank you Andrea. Love that word meander too. I think it’s the name of a river in Turkey!

This Thanksgiving, I will be giving thanks

for Mary-Ann Moore., and so much more.

Blessings, love, Ann Morrison-x

Thank you Ann. I hope your Thanksgiving was a happy one. Blessings to you.