And it was at that age . . . Poetry arrived

in search of me. I don’t know, I don’t know where

it came from, from winter or a river

I don’t know how or when . . .

wrote Pablo Neruda in his poem “Poetry.” Margaret Atwood said it too. Poetry arrived for her one day as she crossed the football field at the University of Toronto. Winnie the Pooh said it this way: “It’s easiest when you let things come.”

I joined the famous and the fictional when a decades-old memory urged itself onto paper almost thirty years ago. The memory began as an image. Then it was a feeling. The lines appeared effortlessly once I wrote the first line down.

When I see a man standing at a drugstore perfume counter

I know he has put off buying a gift for too long

until all the other stores are closed

except the drugstore open until midnight.

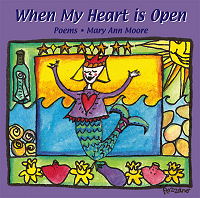

(from “Open Until Midnight,” When My Heart is Open, a CD of poems, Flying Mermaids Studio, 1999, cover art by Maria Pezzano, graphic design by Sarah Clark)

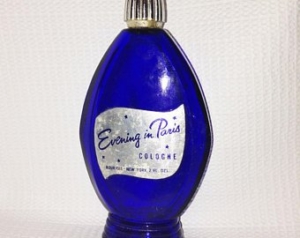

That drugstore scene had occurred many years before and the memory appeared to me to be the man’s longing to please. I saw the little boy in him. I remembered the little girl in me and my own attempts at giving a gift to my mother. I remembered Evening in Paris and its blue bottle. I remembered my son and the unfamiliar territory we entered when I left my marriage and our family. We all felt raw. In new places.

That drugstore scene had occurred many years before and the memory appeared to me to be the man’s longing to please. I saw the little boy in him. I remembered the little girl in me and my own attempts at giving a gift to my mother. I remembered Evening in Paris and its blue bottle. I remembered my son and the unfamiliar territory we entered when I left my marriage and our family. We all felt raw. In new places.

Once I had expressed the feelings in response to that drugstore scene, I let them go. I was saved from carrying the longings and regrets, inside. It doesn’t mean all traces of longing are gone. I had found a way to integrate the memories.

Pema Chodron writes of bodhichitta, the word for “noble or awakened heart,” as that soft spot we all have in When Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice for Difficult Times. The noble heart that feels kinship with all things.

“Whenever we let go of holding on to ourselves and look at the world around us, whenever we connect with sorrow, whenever we connect with joy, whenever we drop our resentment and complaint, in those moments bodhichitta is here,” Pema Chodron writes.

Following the drugstore poem, poems continued to arrive: when I woke up, as I read the newspaper on Saturday morning, as I unpacked spices and put them in a cupboard in a new apartment.

Putting spices away is a pretty ordinary event but it is in the being present, mindful, that an ordinary task becomes exquisite. It’s the noticing that creates the ceremony.

Reading French philosopher, Gaston Bachelard, helped me to define poetry for myself.

Poetry is the soul creating a ceremony out of an ordinary event.

It is in the soul where inner and outer worlds meet. As Allan Coombs and Mark Holland write in Synchronicity through the eyes of science, myth and the trickster (Marlowe & Company, 1996), the soul is “a perpetual living mirror of the universe.” What you delight in or suffer from connects you to others.

Billy Collins, a former poet laureate of the United States, said in an interview following the events of September 11, 2001 that “poetry is one of the original grief counselling centres.” A poem is a place to pour out your longing. In fact, the blank page is like open arms, welcoming your words. As Collins points out though, the poem is more about the reader of it than it is about the writer. “You don’t read poetry to find out about the poet,” Collins said. “You read poetry to find out about yourself.”

A poem that arrives is a gift to the writer of it. It becomes a gift as well to the reader who recalls her own story – and may write another poem in response.

“I don’t know if I breathed the poem or the poem breathed me,” Natalie Goldberg writes in “How Poetry Saved My Life,” the opening essay in Top of My Lungs (The Overlook Press, 2002).

Breath. Meditation. When I lack focus, when I am full of thoughts for the day’s to-do list, I open to a poem such as “Variation on a Theme by Rilke” by Denise Levertov that begins:

A certain day became a presence to me;

there it was, confronting me – a sky, air, light:

a being. And before it started to descend

from the height of noon, it leaned over

and struck my shoulder as if with

the flat of a sword, granting me

honour and a task . . .

The poem helps me honour my day’s work. Brings me back to centre. The moment. The breath.

Where do they come from?

Poems may come from dreams you remember as you awaken. They can appear in that space between sleeping and waking. They find expression in a bowl of sliced fruit sitting in a cut glass bowl.

You can also be inspired by reading another’s poetry. Or by a line you’ve read somewhere. Sometimes, you can create found poems by recording what you’ve heard in a conversation or read in the newspaper.

In the writing circles I lead, I love to share in the delight with people who, given a few prompts, create a poem. Often it’s a well-known poet’s poem that will inspire. Lorna Crozier’s “Packing for the Future: Instructions” has been a favourite example through the years.

Take a leather satchel,

a velvet bag and an old tin box –

A salamander painted on the lid.

Years ago while still living in Ontario, I offered poem making workshops I called “Just Like Making Soup” because there is a recipe, some guidelines, but then you’re free to add your own elements and make that soup your very own. While you’re standing at the stove stirring the soup or sitting at the table writing the poem, you are in the moment while memories of having eaten that soup before, with loved ones, arrive like ingredients on the page.

In more recent years, I’ve offered one-day writing circles called “Poetry as a Doorway in . . . and a Welcome Home.” Poetry can be described as a threshold practice, the realm of the liminal, a word derived from the Latin limen, meaning “threshold.”

As Jane Hirshfield writes in “Writing and the Threshold Life” (Nine Gates: Entering the Mind of Poetry, HarperPerennial, 1997), when entering the liminal, “a person leaves behind his or her old identity and dwells in a threshold state of ambiguity, openness, and indeterminacy.”

“Entrance into the liminal is fundamental to the life of writing,” Hirshfield writes and includes some lines of Czeslaw Milosz from his poem “Ars Poetica”:

The purpose of poetry is to remind us

how difficult it is to remain just one person,

for our house is open, there are no keys in the doors,

and invisible guests come in and out at will.

How to Begin

You could begin with a list such as an alphabetical list of your favourite things. Apples. Biscotti. Carnations. Dogs.

Then, get more specific. What kind of apples and what colour are they? Green Granny Smith.

How about a more exquisite description of green? Try, tart apples the colour of April. As you write the word, you may find the biscotti takes you to a cafe in your city’s Little Italy or to Florence even though you haven’t been there.

Let paint chips, photographs of your vacation, items on your kitchen table help you describe your favourite things.

When I still lived in Ontario, I visited the McMichael Art Gallery in Kleinburg and passed through the children’s section. A board of common household objects hung on the wall as a teaching tool. The children were to use the items such as a spatula, a potato masher, a plate to study shape and perspective for drawing. What a great way to write a poem I thought. Take that potato masher. Look at the green of the handle. The patina of the worn wood. The memories of the hands that held it.

Your poem doesn’t need to rhyme but it needs rhythm and cadence when you read it out loud. Reading poems out loud to hear how they sound is a way to discover that rhythm. As for ordinary things, Pablo Neruda was a master with his odes to common things. Jane Hirshfield has also written about ordinary objects and Lorna Crozier wrote a delightful book entitled The Book of Marvels: A Compendium of Everything Things (Greystone Books, 2012).

My poetry mentor from 2006 until he died on March 7, 2019, Patrick Lane, said: “The poems we write are a looking back, a past we find in the present, the poem expressing what we feel now about what we felt then. As Patrick has also said: “Common objects take on a mysterious presence if we pay close enough attention to them.”

Patrick Lane may be gone in bodily form; his spirit lives on in the fine work he left behind in poetry, two novels and a brilliant memoir. And his teaching will continue as his students continue to write and pass on the wisdom he generously shared with us.

How to End

Save your very best line until the last. We may not learn anything when we read your poem but we need to feel something. We need to hear or read a new way of expressing something familiar.

At a recent poetry retreat with Lorna Crozier, she suggested that the last line of one of my new poems was too “definitive.” She suggests coming up with an image when you’re not sure how to end.

Sometimes, I’ve removed a last line so the poem isn’t neatly summed up. Some things need to be left for the reader to feel.

I end my list of favourite things with Z for Zen:

Stones, water trickling,

my writer’s garden.

Poems by Heart

I was fascinated to hear David Whyte recite his poems and the poetry of others a couple of decades ago on cassette in a friend’s car. He memorizes them and repeats lines several times so listeners can grasp the message.

Kim Rosen was inspired by David Whyte too and began learning poems by heart. Kim offers “poetry dives” in various parts of the world and came to Victoria, B.C. a couple of times. I so appreciated attending her retreats to immerse myself in poetry as well as the music of cellist Jami Sieber who was also there. Kim uses breathwork, improv and so many other aspects from her training to create a fully-embodied experience of poetry.

When Kim’s book came out, Saved by a Poem (Hay House, 2009), she came to Nanaimo to do a presentation and offer a workshop. It’s really lovely to hear her recite “Poetry” by Pablo Neruda (quoted at the beginning of this blog) which she does on CD, Only Breath, recorded with Jami Sieber and other musicians.

It’s so very handy to be able to recite a poem in the moment, no need to have a printed copy with you. My friend Birdie has been learning poems by heart and a favourite of hers is “Wild Geese” by Mary Oliver. I love it too as well as “The Journey” by Mary Oliver:

. . . and there was a new voice

which you slowly

recognized as your own,

that kept you company

as you strode deeper and deeper

into the world,

determined to do

the only thing you could . . . determined to save

the only life you could save.

Poems are gifts. They’re an ancient form of prayer. They express longings. They are the exquisite details of life. They are teachers and companions. Poetry connects us to one another and to ourselves. David Whyte describes poetry as “an incredible lifeline to anyone who’s looking for a community of understanding.”

Poetry is the content of our daily life

The meaning of a poem? While that question may have been posed by our teachers in high school, now I ask, how do you feel when you read it? Read the poem out loud. Remember it by heart. You’ll be inspired to write/breathe your own poem.

It’s putting one step in front of the other, like a walking meditation. Peace is every step as Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hanh says. Let poetry be your expression in your daily tasks, he advises.

Poetry is the content of your daily life

Poetry is always there

when I water my vegetables

when I make my breakfast

poetry is inside of me

and the time you sit down and write it down

is only an expression of it

so the making of poetry is

taking place in your daily life

and sitting down and putting it on paper

is just one of your needs

like going to the bathroom

or brushing your teeth

(from “Calm Abiding: Writers on Buddhism,” Liz Marshall, Director, Producer, Videographer for Book Television, 2002.)

Poetry as a need was expressed in those terms by the late African-American poet Audre Lorde as well, or rather as a necessity, particularly for women, in her essay, “Poetry is Not a Luxury” (Sister Outsider: Essays & Speeches, The Crossing Press, 1996).

Lorde wrote: “It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action. Poetry is the way we help give name to the nameless so it can be thought. The farthest horizons of our hopes and fears are our poems, carved from the rock experiences of our daily lives.”

Muriel Rukeyser who described poems as “meeting-places,” also addressed our fear of poetry in her book, The Life of Poetry (Paris Press, 1996). “A poem does invite, it does require. What does it invite? A poem invites you to feel. More than that: it invites you to respond. And better than that: a poem invites a total response.”

Pablo Neruda, a longtime favourite of mine, wrote poems for the newspaper so they would be accessible and went underground to meet with miners to recite poetry to them.

A Community of Poets

Tofino’s poet laureate, Joanna Streetly, has been posting a poem a day on her website for National Poetry Month. She posted mine there on April 4th: “Sure-as-Morning.” Joanna described me as being dedicated to the sharing and enjoyment of poetry and community. She is so right!

One of the main components of the community I’m dedicated to is the writing circle. For over twenty years, I’ve been leading women’s writing circles and at times, all-day circles and retreats. The weekly circles, called Writing Life, offer a place for voices to be heard. We create a sacred container together with some guidelines so voices, stories and poems can be honoured.

Rumi and other Sufi poets wrote about the gulistan, the rose garden, and paradise. The Persian word for “paradise” means “a walled garden.” A protective enclosure and a place of beauty where each flower has a place, not any more special than the one next to it. Humble in its shining.

It’s important to create that protective enclosure and to embrace creativity as I believe it connects us to a magnificent spiritual system.

Matthew Fox, Episcopal priest and author of over many books including one on creativity, says to find, honour and practice creativity we need to learn to praise. In fact that is what we do when we write a poem. Here is what Patrick Lane had to say at one of the poets’ retreats I attended with him some years ago:

We are left with praise at the end, for what else is there we can hold to in the face of the terrible, the beautiful world? Nothing is wasted, if suffering teaches us how to live. Surely there is some glory we can grasp, some beauty we can hold to in our grief and joy. You too, who dwell in the quiet places, the dark rooms and the sunny meadows, you too must come to this place where we can say, “let all men believe it”. [as William Carlos Williams wrote in his poem “To a Dog Injured in the Street”. ] The “it” we are encompassed by [is] what we have to hold to in the end. Sometimes all we have is a stick to place upon a fire, a spoon to lift to our own or to another’s lips, a flower we do not pick, but praise for its desire to be but one of an ongoing flourishing of flowers, the bee comes gladly to lay the pollen upon the stamen, the night pushed back, the day begun, the good seed growing, life renewed.

Praise, yes. Praise.

Dear Mary Ann – Thank you for your beautiful posting. I was up early this morning, the sun rise so beautiful. Nature and your words — the two things that brought bodhichitta into my life this morning.

Blessings,

Dear Mary Ann – Thank you for your beautiful posting. I was up early this morning, the sun rise so beautiful. Nature and your words — the two things that brought bodhichitta into my life this morning.

Blessings,

This is such a rich and beautiful essay on the meaning of poetry. Thank you, Mary Ann.

Marlene Dean

What a wonderful compendium of poetry—its origins, purpose, and power! Praise be.