The theme of the current Writing Life women’s circle is Bask in Possibility. I’ve found it to be an enlivening theme for the writing circle and the new year.

“And our hopes such as they are / invisible before us / untouched and still possible,” poet W. S. Merwin wrote in his poem, “To the New Year.”

I chose a word for the new year: STOP. For me, that stands for Soulful Turning Off Practice. Rather than try to do more, I figure turning off technology and turning off the need to do anything would be a good break during the day. Maybe that soulful pause will stretch into something longer – a whole day or even more.

The soulful pause, I think, will be a good antidote to overwhelm and so will “bask in possibility.” Rather than be overwhelmed by the “to do” list, I can see various events, tasks, and responsibilities as possibilities. I think my improv training is having very good effects on my everyday life!

It’s easy to become overwhelmed these days with the deluge of information coming our way in various forms. We’re not left to muse and wonder as answers are at our fingertips. I still like the musing though and the process attracts me more than the product when it comes to writing.

I was inspired by what visual artist Sheila Norgate had to say about separating her self-esteem from the sale of her art. (See my last blog entitled “Strange Bedfellows.”) “The impulse to make art that came over me in the early 1980s, had nothing to do with money. The calling was pure, and loud, and flooded with uncontaminated devotion,” Sheila wrote.

When it comes to writing, Elizabeth Gilbert, the author of Eat, Pray Love and a beautiful novel, The Signature of All Things, had other jobs besides writing before she became well known. She would receive rejection letters from publishers and knew that rewards couldn’t come from external results.

When it comes to writing, Elizabeth Gilbert, the author of Eat, Pray Love and a beautiful novel, The Signature of All Things, had other jobs besides writing before she became well known. She would receive rejection letters from publishers and knew that rewards couldn’t come from external results.

“The rewards had to come from the joy of puzzling out the work itself, and from the private awareness I held that I had chosen a devotional path and I was being true to it. If someday I got lucky enough to be paid for my work, that would be great, but in the meantime, money could always come from other places.”

Liz Gilbert says in a chapter entitled “Taking Vows” in Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear (Riverhead Books, 2015) that she took vows to become a writer when she was about sixteen years old. She invented her own ceremony, lit a candle, got down on her knees and “swore my fidelity to writing for the rest of my  natural life.”

natural life.”

“My vows were strangely specific and, I would still argue, pretty realistic. I didn’t make a promise that I would be a successful writer, because I sensed that success was not under my control. Nor did I promise that I would be a great writer, because I didn’t know if I could be great. . . . Instead, I simply vowed to the universe that I would write forever, regardless of the result. I promised that I would try to be brave, and grateful, and as uncomplaining as I could possibly be. I also promised that I would never ask writing to take care of me financially, but that I would always take care of it – meaning that I would always support us both.”

Why try to publish when “rejection” is a very likely possibility? Someone engaged in the process of writing, uncovering their own story for themselves, may ask that question. The writer part of you who may choose writing as a “devotional path” as Liz Gilbert says or as a spiritual practice as I describe it, is very different from the part of you with the skill and stamina needed for the marketplace.

In an article entitled “Keeping a Writer’s Soul” by Marianne Williamson published seventeen years ago, she wrote: “The part of you that writes does not speak the same language as the part of you that negotiates a contract.” All of that is exciting, she does admit: an agent taking you to lunch, for instance, and selling your book to a publisher. She suggests not taking any of that too seriously as “the more you bow to the powers of the world, the less powerful you will be.”

Publishing has many benefits besides money and that’s what I’ve found most appealing – the opportunity to be part of a larger community of writers doing readings together, organizing festivals, getting together for a chat about the writing life. One of my favourite pastimes is gathering monthly with a group of Nanaimo and area women writers for brunch to chat for a couple of hours.

Another possibility with publishing is, there are readers who will benefit from your story. You find out you’re not alone and so will they.

I have found that working with an editor really gives me a sense of valuing my work. Those editors could be fellow poets, master teachers at a workshop, or editors for literary journals, newspapers or at a publishing house where my writing has been “accepted” and is being readied for publication.

You can also hire an editor before you send out your proposal or manuscript to an agent or publisher. In fact, that’s become more of a necessity these days.

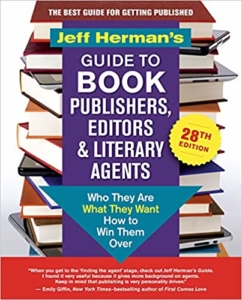

In Jeff Herman’s Guide to Book Publishers, Editor & Literary Agents, 28th edition, (New World Library, 2018), there’s a section on “Independent Editors.” In this latest edition of the guide, there are a couple of new chapters: “When to Call the (Book) Doctor” by Sandi Gelles-Cole and “Trust and Perfect Fit” by Michael Wilde.

In Jeff Herman’s Guide to Book Publishers, Editor & Literary Agents, 28th edition, (New World Library, 2018), there’s a section on “Independent Editors.” In this latest edition of the guide, there are a couple of new chapters: “When to Call the (Book) Doctor” by Sandi Gelles-Cole and “Trust and Perfect Fit” by Michael Wilde.

As Gelles-Cole points out, an editor was traditionally provided by the publisher. That is no longer the case. While some writers seek editorial assistance once a manuscript is completed, Gelles-Cole suggests, particularly in the case of non-fiction, working with an editor to help develop your idea. That editor can also help you with your book proposal.

Independent editors help novelists with their fiction (I know a few writers who have gone that route) and there are poetry editors who assist poets with their manuscripts before they are sent to publishers. Gelles-Cole is a member of the Book Editors Alliance which you can find online: bookeditorsallliance.com.

Jeff Herman’s Guide is a valuable tool if you’re wanting to stretch your wings into the publishing world. The guide begins with a section entitled “Advice for Writers” in which there are chapters such as “Write the Perfect Query Letter” by Jeff Herman and Deborah Herman and “The Knockout Nonfiction Book Proposal.” These are essentials for introducing one’s work to publishers or agents.

A new addition to the latest edition is “The Business of Writing” by Jeff Herman in which he describes working with an agent. Included is an example of the agency-author agreement Herman uses at The Jeff Herman Agency LLC.

There are listings for 104 literary agencies and 176 individual agents. There may be more agents than are listed but they may not have taken the time to complete Jeff Herman’s survey. To his knowledge, Herman has not included agents who charge a fee for reading a manuscript. He says: “Real agents don’t make money from reading your work; they make it from successfully selling your work to a traditional publisher for a 15 percent commission.” There are a few “acceptable exceptions to this rule,” he says. A couple of agents are included in the list who charge less than $100 “in order to defray the cost of employing people to do first reads.”

The agents in the list have answered several questions including the titles of books they’ve recently “agented,” the kinds of books they want to agent, and their views on self-publishing. Michael Carr of Veritas Literary Agency says about self-publishing: “It a great option for a lot of writers. One of my most important clients is a hybrid writer, with an indie series and books he writes for a traditional publisher. That’s a good model for a prolific writer.”

A section entitled “Publishing Conglomerates” describes “The Big 5” which used to be the Big 6 until two of them, Penguin and Random House, joined in 2013.

“Independent Presses” is a section that includes publishers like New World Library, the publisher of the guide, and others like Chronicle Books, Hay House and New Harbinger, distributed by Raincoast in Canada.

Canadian publishers aren’t included in this American guide as Jeff Herman says “they’re not allowed to publish original books written by non-Canadians.” That may because there are independent Canadian publishers receiving government funding in the form of Canada Council grants. (I still have the Jeff Herman’s Guide from 2107 which includes a listing of Canadian publishers as well as U.S. university presses.)

The world of publishing or preparing for it is very different from sitting alone in a room at one’s desk. But that’s where it all begins. Rather than be overwhelmed, try to embrace all the possibilities.

Inspiring Mary Ann and very insightful. So love to read about your word for the year and how it evolves for you and how you then live with it and let it guide you in the days that follow. Thank you for writing and sharing in this beautiful way.