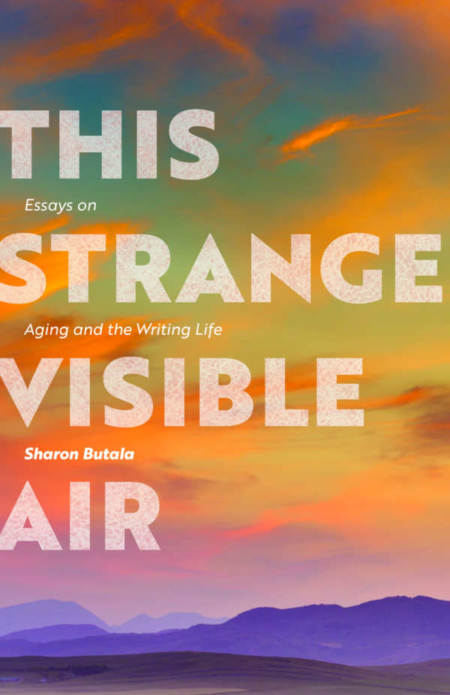

Sharon Butala’s husband died when she was two weeks short of her sixty-seventh birthday she says in the first essay, “Against Ageism,” in her new book of essays on aging and the writing life: This Strange Visible Air (Freehand Books, 2021).

As she was born in 1940, Sharon is 81 years old this year. She has been on her own for over a decade and writes of loneliness in “Open Your Eyes” saying: “I was lonely because I had no significant other reading the newspaper in the other room.”

Sharon recalls being eight years old, living in a village in central Saskatchewan, as a little girl. One “hot Friday afternoon in June,” she wandered off from a softball game being organized on the baseball diamond. She knew, as a small child and not athletic, she’d be the last chosen for any team.

On the front steps to the empty school, Sharon sat alone. Although an older girl had seen her there, either she didn’t let anyone know or if she told a teacher, the teacher chose to leave Sharon alone.

From research Sharon has done about loneliness, she shares a quote by Judith Shulevitz from The New Republic in 2013: “And yet loneliness is made as well as given, and at a very early age. Deprive us of the attention of a loving, reliable parent, and, if nothing happens to make up for that lack, we’ll tend toward loneliness for the rest of our lives. Not only that, but our loneliness will probably make us moody, self-doubting, angry, pessimistic, shy, and hypersensitive to criticism.” It’s a passage that Sharon says, caused her to freeze, “so accurate a description it was of how I gradually, over my adulthood, have come to see myself.”

At the end of her essay, Sharon asks, “But if my teacher had rescued me from my desire for solitude, and my self-willed loneliness, would I be a writer today?”

Burning the Journals

As many of us grow older, we wonder what will happen to our handwritten journals. Sharon has a gas fireplace so went to a friend’s house who had a wood-burning fireplace where she could burn her journals. She says in “Cold Ankles”: “The journals so embarrassed me that I decided to burn them all while I still could, the elderly person on her own being all too well aware that at any moment the Great Catastrophe can strike.”

Stopping to read some of the dreams she had recorded on the journal pages before she threw them into the fire, Sharon saw that some of them “turned out to be prescient.”

The title of the essay is from this passage: “Last night I caught myself thinking I should buy some new socks, as winter is approaching, and my ankles are already cold.”

As for the journals, she says: “And I can’t tell you, even now, if burning my journals was a good or a bad think to have done. If burning my journals changed anything, about the life they recorded or my life to come.”

An Unsolved Murder

I’ve read other books by Sharon Butala and particularly appreciated The Perfection of the Morning: An Apprenticeship in Nature, one of her early nonfiction books. I haven’t read The Girl in Saskatoon: A Meditation on Friendship and now I’m especially curious. Sharon writes of the subject of that particular book in her essay: “The Murder Remains Unsolved.”

“2021lmarks fifty-nine years since beauty queen Alexandra Wiwcharuk was beaten, raped, and murdered, and her body buried in a shallow grave in a copse of trees near the weir on the northeast bank of the South Saskatchewan River in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.”

A few weeks before the discovery of her murder, Alexandra had turned twenty-three; she had graduated from nursing school and was employed at Saskatoon City Hospital. Sharon was fourteen when she met Alex and although they weren’t friends, they knew one another from high school activities.

The murder was never solved and while no harm came to Sharon as she was researching her book over a period of ten years, there was some harassment by phone and other close encounters with cars. Men she wanted to talk to avoided her. And someone anonymously “said that I would be killed if I kept on asking questions . . . “

Sharon says she learned about corruption, class, misogyny and evil. “Also, slowly, over the years, I have begun to see better what I specifically need to fear, and to separate most of that from what doesn’t need to be feared. Now, at eighty, my fears come mostly (but not all) from being an old woman in an old-woman-hostile world.”

The Writing Life

In “Vanished Without a Trace,” Sharon describes her writing life. She published her first book, a novel, in 1984 when she was forty-four. She had begun to write at thirty-eight, leaving her plan to be a painter, behind.

Sharon was a cattle rancher’s wife and rose at 5 a.m. as her husband did, going to her desk to write for two to six hours every day, “weekends and holidays included.” As she “lived in the middle of it,” Sharon wrote about rural western Canada.

“I gave up everything for writing, “she told a television interviewer. And while she thought one night, that she would give up her writing for her husband, child, mother, sisters or friends who needed her, she later acknowledged she was a “liar.” What came to Sharon was the knowledge, “that I would always put my writing ahead of any other significant demand on me; that there was nothing and nobody for whom I would s stop.”

It’s startling to realize that although she says her “sales record was still good enough to get me a publisher,” the ten percent she received “wouldn’t pay the rent, and the big-money prizes continued to elude me.” No wonder writers need to have speaking gigs, work in bakeries and bookshops, or teach.

In 2018, the Writers’ Union of Canada reported that writers’ “incomes had dropped twenty-seven percent since 1998; eighty-one percent of writers now had incomes below the poverty line; worse, female writers now earned fifty-five percent of what male writers earned.”

In August 2007, when her husband Peter died, Sharon “became the sole owner of a bank account that, if it did not make me rich, left me able to live as I always had . . “

At the end of her seventies and in good health, Sharon says in her essay that she is having “a burst of late life creativity.” She tells friends: “I haven’t much time left; I have to get everything down before I depart.” What keeps her writing is the same motive she began with which is: “I continue to have ideas that I need to explore through writing. I can see no reason to quit, for what else would I do with myself? After years of the hardest struggle, the misery of it, the pain and the doubts each day as I tried to find the right words for the idea whose shape I was struggling to reveal, writing is coming easily now, and flows.”

Perhaps Sharon has given up the award and contest-winning aspect of writing and is finding courage and solace in her writing. I know that writing will remain for me the way I make my way through life and I appreciate being in circles where we write together and share aspects of our queries and our discoveries.

Sharon’s final essay, “On the Pandemic” dated May 28, 2020, was written during the early months of the pandemic. At that time, she knew no one who was ill and no one who had died. As an introvert, life during “lockdown” wasn’t all that much different for her. She did wonder though “which would happen first: the gradual lessening of the lockdown, or our complete descent into insanity.”

Hopefully it was the gradual lessening of the lockdown so that Sharon could see her friends again. Sharon has calculated how many years she has left and I find myself thinking of that as well. Most important, is how we spend our days: writing, not for any awards, but because we need to. And while we’re at it, we can celebrate the desire and imagination that continues to nourish us.

Hopefully it was the gradual lessening of the lockdown so that Sharon could see her friends again. Sharon has calculated how many years she has left and I find myself thinking of that as well. Most important, is how we spend our days: writing, not for any awards, but because we need to. And while we’re at it, we can celebrate the desire and imagination that continues to nourish us.

Lorna Crozier, another Saskatchewan writer based for many years in North Saanich on Vancouver Island, says: “Oh, help me find the mettle to resist the call to go quietly into that good night. No matter how many years under my belt, may I have the audacity to open my mouth and wail. In the same essay, “Running/Writing For Your Life” (The New Quarterly, Summer 2021), Lorna says: “How will I touch with words those places aging makes tender. I don’t know, though I started to do that about three books ago. What I do know is that the days are shrinking, and that as I set out into the lengthening dark, it is a journey I must embark on alone.”

Still, Lorna will continue because as she says: “I can’t imagine a life without poetry, without writing poetry, I have to believe that the sheer wild joy of it will lead me to places I haven’t gone before, places where I can discover some shard of beauty, whether painful or joyous. These are the risks I take, the nerve I ride on.”

It’s true that beauty discovered may be painful or joyous. We remain curious. As John Gould says of This Strange Visible Air by Sharon Butala: “The insight embodied in this book doesn’t come free with age, but as the payoff for decades of fine attention, of impassioned curiosity.”

Hi Mary Ann, I really enjoyed reading this review and your reflections in it. It’s very inspiring and thought-provoking too! I took a memoir writing course with Sharon Butala years ago at Hollyhock. That project got tucked away and has recently been dusted off again and I’m ready to give it my attention each morning at 5 AM. Knowing that other women are up then to engage in their writing lives, inspires me to rise early and keep going. Thanks for all you do to support writers, poems and books. Thanks for your writing in the world!

Thank you for your comments Lynda. I’m very glad you’re tending to your project at 5 a.m. Yikes! I thank you for all your support of writers through your books, coaching and the International Association for Journal Writing as well as taking the time to leave comments here.

Really enjoyed reading this review, MaryAnn. It is inspiring to read about Sharon’s writing career. Your work as a writer and the ways you support other writers is also very inspiring. Thank you for sharing so much.

Thank you Beth! I appreciate your comments and I’m grateful that we met through our shared love of writing.

Thank you for this interesting reflection on Sharon Butala. I too did a memoir workshop many years ago with Sharon at Hollyhock.