While thinking of the various ways women’s hands have created so many beautiful things (I wrote a poem called “Women’s Hands”), I’m also exploring personal essays and their various forms. As it turns out, the two go very well together and share common threads so to speak.

Sarah Minor’s essay “What Quilting and Embroidery Can Teach us About Narrative Form” appeared first in Creative Non-Fiction Issue #64 and I found it online at Literary Hub.

Minor says, as a nonfiction writer, the snatching of lost memories “reminds me that the narratives we live inside are never linear from the start. Our stories are patterns of experiences, a few knit together and the vast remainder discarded as scrap. She mentions the “braided essay” where past and future are visited, by the reader, alternately “skipping across time and space as if following the path through a distracted mind. But the real beauty of a successful braid is how the ‘threads’ combine thematically to form a more complete and pliable piece of nonfiction.”

In a section of Minor’s essay entitled “Quilted Essays,” she describes the domestic art of quilting. “In many cultures, quilts act as historical documents that preserve narratives about place and identity. A scholar named Mara Witzling has written that quilts historically “enabled women to speak the truth about their lives”, by joining many disparate fragments. Some of the fragments sewn into the quilt could have been inherited from ancestors.

Quilters “piece” together sections of fabric with even stitches beginning in the middle as is the case with many traditional patterns. As Sarah Minor says: “As a material metaphor for nonfiction, writers interested in new forms might consider ‘piecing’ sections of text as a means of working outwards from a kind of center. This center could be the most significant or challenging moment in an essay.”

Under the heading of “Stitching a Scene,” Sarah writes about embroidered pieces like tapestries and appliqué samplers that “have recorded the types of personal narratives that were never saved on paper.”

Embroidery requires floss, “a material richer in color and more texturized than sewing thread.” In considering the literary equivalents of floss, Sarah Minor notes “the rich and often brief lines of a memoir that we pause over – the lines that shine because they appear in small patches that might overwhelm the piece if overdone – and writers might also learn from embroidery how to massage a revealing description into a hard knot of facts.”

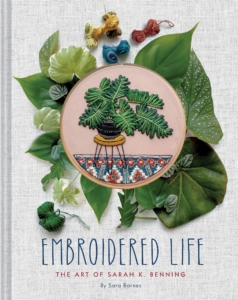

And I’ve discovered another couple of Sarahs: Actually one of them doesn’t have the “h.” Sara Barnes is the author of Embroidered Life: The Art of Sarah K. Benning (Chronicle Books, 2019). Barnes is a freelance writer and artist who has a blog: Brown Paper Bag at www.brwnpaperbag.com where she includes illustrations of the work of various artists of embroidery and other media as well as her own work.

And I’ve discovered another couple of Sarahs: Actually one of them doesn’t have the “h.” Sara Barnes is the author of Embroidered Life: The Art of Sarah K. Benning (Chronicle Books, 2019). Barnes is a freelance writer and artist who has a blog: Brown Paper Bag at www.brwnpaperbag.com where she includes illustrations of the work of various artists of embroidery and other media as well as her own work.

Sarah K. Benning is a contemporary embroidery artist who creates highly detailed, hand-stitched works, writes DIY patterns for other embroidery practitioners and teaches workshops all over the world. She has an ETSY site for selling digital patterns and I see right now, she’s taking a break. You can sign up by email to be notified when she’s back in business if you’re wanting to stitch stories as well as embroider on fabric. The featured image at the top of the page is by Sarah Benning, embroidered in early 2016 when she lived in Menorca.

Embroidered Life’s beautiful design is by Kayla Ferriera with the photography done by Sarah K. Benning. A three-dimensional reproduction, machine made, of Benning’s “Elephant Ear and Rug” is on the front cover. Pretty ingenious I’d say.

Contemporary embroidery, as the book’s author Sara Barnes points out, is firstly “a celebration of color, texture, and material” and secondly, uses “thread to illustrate a story.”

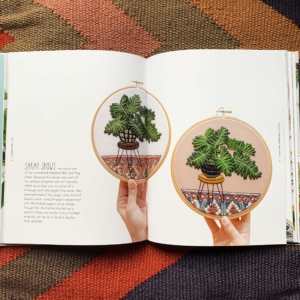

Benning is largely self-taught and considers her embroidery technique an “illustration practice that happens to be in thread.” Her thread of choice is DMC embroidery floss. “With nearly five hundred colors, she has a ton of different greens available to stitch any plant she likes.” And it’s plants, as you’ll see in the illustrations, that she loves to stitch.

My mother did a type of stitching called crewel work. I have many examples of her work in the form of a tea cozy, a bell pull, a cushion cover. Crewel work is a form of embroidery as Barnes points out: “using worsted yarn in two twisted strands – in muted shades of greens and blues, as well as terracotta, buff, red, and yellow.

The Bayeux Tapestry, as we refer to it, is actually a detailed work of embroidery. It provides an account of the Norman conquest of England in 1066 in pictures and there are “medieval Latin inscriptions, called tituli, that narrate each scene.” The nine linen panels were completed by a professional embroidery workshop to stitch “this journal in thread.”

Sarah Benning started stitching the plant pieces as “little replacement and memorial pieces.” (Sarah had many indoor plants die one winter.) She uses the satin stitch primarily, “a basic technique that uses a series of flat stitches to cover the fabric.”

Sarah Benning started stitching the plant pieces as “little replacement and memorial pieces.” (Sarah had many indoor plants die one winter.) She uses the satin stitch primarily, “a basic technique that uses a series of flat stitches to cover the fabric.”

Benning draws an image on fabric using an ordinary pencil. She “typically loads her needle with three strands of DMC thread folded onto itself – making six strands total.” To keep things organized, Benning keeps bundles of thread in baskets of colour-specific skeins wrapped in a butterfly shape.

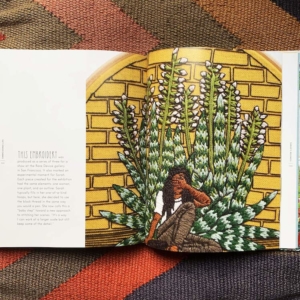

Figures first appeared in Benning’s work in the spring of 2016. She was living in Spain at the time and “the women in her embroideries were her way of subtly expressing her loneliness.”

On Valentine’s Day 2018, Benning released a pattern with a company called A Beautiful Mess. It features a motif of heart-shaped cacti and is a beginner-level design. Embroiderers can complete the pattern in the hoop or take the heart-shaped elements and embroider them onto clothing items or a tote bag.

On Valentine’s Day 2018, Benning released a pattern with a company called A Beautiful Mess. It features a motif of heart-shaped cacti and is a beginner-level design. Embroiderers can complete the pattern in the hoop or take the heart-shaped elements and embroider them onto clothing items or a tote bag.

(See the heart-shaped cacti in the hoop with a pink background in the photo.)

The embroidery to the left, with the figure of a woman, was produced as a series of three for a show at the Rare Device gallery in San Francisco.

The embroidery to the left, with the figure of a woman, was produced as a series of three for a show at the Rare Device gallery in San Francisco.

“Practice makes comfort” Benning says as the more you repeat a stitch, the better you’ll be at it. To Benning, embroidery is supposed to be fun and enjoyable. “To me, getting too wrapped up in technique becomes paralyzing and takes the joy out of it.”

Whatever route we take piecing together our stories with words or embroidering them with threads, we ought to enjoy the process.

From a young age, I learned to love things made by women’s hands:

From a young age, I learned to love things made by women’s hands:

smocked dresses, knitted mittens, quilts with star patterns,

a birdhouse crafted out of a shredded wheat box by Evelyn Goodwill,

my great aunt’s friend who travelled with her.

From “Women’s Hands”

Mary Ann Moore

“Women’s Hands” is a fold-out poem by Mary Ann Moore, designed by sarah j. clark.