Sara Graefe, editor of Swelling with Pride (Dagger Editions, 2018) and “proud queer mom,” assembled more than twenty-five creative non-fiction LGBTQ2 authors from across North America for the book sub-titled Queer Conception and Adoption Stories. Sara lives with her wife and school-aged son in Vancouver and is on faculty in the Creative Writing Program at the University of British Columbia. As Sara says in the introduction, “There’s no straightforward path to LGBTQ2 parenthood.” She found the curating of the collection to be healing work and a privilege to work with queer women, trans and genderqueer folk who shared intimate stories and experiences that were life-altering.

It’s an amazing collection of stories of the various hurdles the contributors had to overcome to attain their passionate desire for parenthood. There are exceptions to the end result. For Marusya Bociurkiw who planned to adopt a teenager, the young woman, Cindi, left three months after moving in. Marusya who is an associate professor at Ryerson University, acknowledges in “Attachment Roulette” what she taught Cindi and what Cindi taught her.

Another adoption story is Patrice Leung’s “Pathway.” It was the early 2000s when Patrice, a single lesbian, travelled to China with her sister to adopt her first daughter. She had been told that the Chinese government required a notarized declaration that she wasn’t a homosexual. “Our first few years together were so arduous I felt sorry for us both,” Patrice says of herself and her daughter Keala. She realized Keala needed an ally and Patrice went back for daughter number two, Tasia.

Susan G. Cole is a name I know from my Toronto days. She is a writer, editor and activist whose play, A Fertile Imagination about two lesbians trying to have a baby, was nominated for two Dora Awards. She is Books Editor at Now Magazine and I’ve seen Susan’s column, “Cole’s Notes” in Herizons. Her essay begins in 1985 when her brother Peter agreed to a sperm donation for Susan’s partner Leslie. At that time, sperm banks were charging “ten thousand dollars a pop.” And don’t call a syringe a turkey baster she says. “That giant utensil simply will not work.” Leslie had a miscarriage during her fifth month of pregnancy and Susan writes about its “high frequency,” how seldom it’s talked about and the “extent to which the trauma is easily dismissed.”

Susan and Leslie’s daughter Molly was born in 1987 at a time when they were the only lesbian couple they knew with children. Molly is now married and learned at seven years of age that her loving uncle Peter, who has since died, was her sperm donor.

Vici Johnstone is the publisher at Caitlin Press where Dagger Editions is an imprint “dedicated to publishing literary fiction, non-fiction and poetry by and about queer women, including trans women or trans men, or anyone who includes this in their personal history.” Vici did the book’s text and cover design with art work by Steve Gribben.

Vici gave birth to her son Dannen in 1990. She acknowledges two women, Penny and Sue, of the Lesbian Mothers Defense Fund (LMDF) for helping with “running sperm in a double-blind scenario for other couples, so that their anonymity could be completely maintained.” She split up with her partner of that time and Vici gained sole custody of Dannen following “a bitter legal battle.” Two gay male friends were among the donors; one has remained constant in Dannen’s life.

As Janet Madsen points out in “Circumstances Beyond Our Control,” being a queer couple wanting to reproduce means you need a missing ingredient i.e. sperm and “you have to accept other players in what is usually an intimate process.” At a Canadian fertility clinic, Janet was required, before starting insemination, to have an HSG, an x-ray of the fallopian tubes which she says “hurts like hell.” She and her partner Tracy live with their two teens in Vancouver.

I remember having the test in about 1972 during which dye is inserted into the fallopian tubes to see if they are blocked. In my case, it set off an infection and I was ill for six months.

“The Queer Baby Project” is by Susan Meyers and daughter Kira Meyers-Guiden. Although some of the contributors to the anthology tried to add pleasurable elements to insemination with a syringe, Susan refers to the “florescent lights, a gown, scrunching along the crinkly paper, and stirrups.”

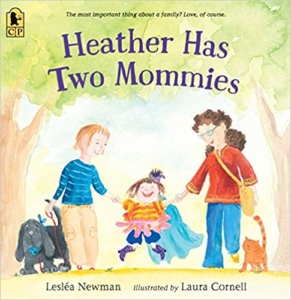

Heather Has Two Mommies by Leslie Newman has been the most popular, and probably the only book for awhile, for kids with two lesbian mothers. Kira thought all her friends in kindergarten were reading the book and was shocked when they didn’t get what she was telling them. She says: “I’ve known from a young age that all families are different, and that shared blood is not a necessity for a family.”

Heather Has Two Mommies by Leslie Newman has been the most popular, and probably the only book for awhile, for kids with two lesbian mothers. Kira thought all her friends in kindergarten were reading the book and was shocked when they didn’t get what she was telling them. She says: “I’ve known from a young age that all families are different, and that shared blood is not a necessity for a family.”

Susan was the “other mother” when her partner Barb gave birth to Kira who says “Growing up, Mother’s Day was a big deal in my house.” When she announced to her granddad that she would be getting married to her long-time female partner and even though he had been part of Kira’s life for as long as she had been alive, “he knew the children of lesbians would continue this shameful lifestyle.” She chose not to have him part of her life anymore and says: “My queerness is my own and is not a negative reflection of my moms. If anything, they provided me with a household where I could be myself without judgment.”

In 1995, Susan and Barb attended the Unified Family Court in Kingston, Ontario to be granted “the privilege of both becoming the legal parents of our daughter.” They, and lesbian parents before them, wanted the court to ensure that both parents were legally viewed as such, using adoption measures “like those often used by heterosexual step-parents to grant legal parenthood to the non-biological mom.”

In January 2017, the All Families Are Equal Act was proclaimed in Ontario, “ensuring that same-sex parents who use a sperm or egg donor or surrogate are legally recognized as parents.”

Emily Cummins-Woods is a social worker who lives with her partner and children in Kingston, Ontario. She gives the full name of the HSG: hysterosalpingogram, and says: “I wouldn’t wish it on you even if you are a truly wicked person and/or get pregnant really easily.”

“We put our bodies, souls and our relationship on the line for a wish of the heart,” Emily writes and the same could be said of the other contributors who were or are in relationships and wanting children. It’s emotionally costly and financially as well. “It was recommended to use two vials per cycle, which totalled fourteen hundred dollars per month! We got a line of credit,” Emily writes.

Emily didn’t get pregnant so her partner Alice “whipped through the fertility obstacle” course and got pregnant with sperm from a known donor. He was married to a woman and they didn’t have children or want any themselves. And then Emily got pregnant with the same donor’s sperm. Each of their sons has his own “bio-mom.”

Jane Byers, of Nelson, B.C., and her partner adopted twins who had been with their foster parents for the first fourteen months of their lives. “What if Your Kids Grow Up to Be Straight” is the title of her essay and a question the foster parents asked when Jane and her partner were getting to know the twins before they went to live with them. They’re nine years old now and see their foster parents as Nana and Papa. In answer to their earlier question, Jane says: “I believe our respective answers would be the same to both questions [including What would you do if your kids grow up to be gay]: love them, shine them up and celebrate their identities no matter what.”

Nicole Breit’s “The Difference Between a Hard and Soft C” is a beautiful essay written in what she may call a CNF (creative non-fiction) “outlier form”about “Love for a woman, desire for a man – not apples and oranges. Chardonnay and crème brule.”

Nicole Breit’s “The Difference Between a Hard and Soft C” is a beautiful essay written in what she may call a CNF (creative non-fiction) “outlier form”about “Love for a woman, desire for a man – not apples and oranges. Chardonnay and crème brule.”

She lives in Gibsons, B.C. with her wife and two children and is an online creative writing instructor of writing programs called Spark Your Story.

“Love, friendship, sex – categorical boundaries that blur so easily for me. But I can distinguish my feelings.” She always believed “a third didn’t have to destroy us.”

“The beauty of outsider privileges: we make our own rules,” Nicole says in Part 9 of her essay.

Eamon MacDonald, a researcher, educator and political theorist in Kingston, Ontario writes in “This Road”: “I could have a child, I have told myself. It’s the one thing that this female body of mine can do that might make sense of the fact that I was born female. Or, I could begin the road to transition.”

Eamon does become pregnant with the sperm of a gay male friend. Eamon’s female partner though doesn’t want a partner who understands themselves to be “not female, not a woman” and someone who was a mother. Eamon’s daughter is in her mid-twenties and the essay is addressed to the unnamed man who has been a valued friend and family member all along. “What I do know is that there are a lot of ways to be friends and a lot of ways to be family.”

“Now I find myself in a community where my trans-ness is welcomed, where I can be both myself and somehow also a mother,” Eamon says.

Andrea Bennett shares an apartment with her partner Will in Little Italy in Montreal. She grew up in a suburb outside Hamilton and describes herself as “a gender non-conformist since I was a kid”. In her essay, “Like a Boy, But Not a Boy: One Experience of Non-Binary Pregnancy,” Andrea writes: “The two little lines on the stick showed up nearly two decades after I’d set thinness, femininity and girlhood aside and decided to accept myself for who I was.”

She wondered in university if she was a “straight butch” and later came across the term “non-binary.” She and Will both wore suits at their wedding with “gender-neutral vows.”

The book has more essays including “The Birth Video” by Rachel Epstein who had an “an eleven-person birth team” in 1992. A video was made of her giving birth to her daughter Sadie at home, later used as a teaching tool. Rachel is a long-time LGBTQ+ parenting activist, educator and researcher. I remember Rachel leading a lesbian theatre group I was part of where we did lots of improv and I’ve been a fan of improv, as a participant, ever since.

I ought to add that having the HSG revealed blocked fallopian tubes and I didn’t suffer what some of these contributors did in terms of miscarriages, ectopic pregnancies, a still birth, or an adoption breakdown. I have two adopted children: a son and daughter born in 1973 and 1977 respectively. We’re all looking for happy endings.