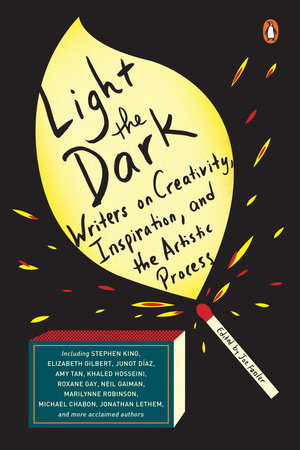

Poet Billy Collins, when discovering William Butler Yeats’ poem “The Lake Isle of Innisfree,” found it to have “immediate appeal.” Billy’s essay, “Into the Deep Heart’s Core,” was the first one I read in Light the Dark: Writers on Creativity, Inspiration, and the Artistic Process (Penguin Books, 2017). I’m a fan of Billy Collins and his poetry and wanted to find out what inspires him.

As it turns out, Billy finds pleasure in memorizing a poem. He writes: “When you internalize a poem, it becomes something inside of you. You’re able to walk around with it. It becomes a companion.”

Wherever he is, Yeats hears “lake water lapping with low sounds by the shore” even when he’s on “the roadway, or on the pavements grey.” The final line of the poem is: “I hear it in the deep heart’s core.” Collins interpreted that as: “I want to go somewhere better than where I am.”

Billy found that when having an MRI some years ago, he opted not for the music which might have been “Neil Diamond classics or something” but opted to recite to himself “The Lake Isle of Innisfree.” He took different approaches to reciting it such as saying just the rhyming words or saying every other line. By the time the MRI was over, he was in the process of saying it backward. “And the poem – like a good companion – had saved me from really freaking out.”

Rather than “the pavements grey,” one can hear “the call of a safe, peaceful place, especially while under duress,” Billy suggests: while lying in the MRI, in jail for the night, or while stuck on an elevator. “Once you’ve installed the poem in your memory, it’s there to comfort you – or at least distract you – wherever you are.”

“Poetry becomes an oasis or sanctuary from the forces constantly drawing us into social and public life,” Billy says. He had read that “we’re not suffering from an overflow of information – we’re suffering from an overflow of insignificance.”

I’ve always liked “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” too and it would be a good one to learn by heart. There is the option of “spa music” while having an MRI and reciting “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” may go along really well with it.

In his preface to the book, editor Joe Fassler makes note of Orhan Pamuk’s novel The New Life in which this line appears: “I read a book one day and my whole life was changed.” It appears to be true for the writers whose essays appear in Light the Dark.

The collection of essays grew out of “By Heart,” an online series Joe created for The Atlantic in 2013. He asked working artists to choose a favourite passage from literature, “the lines that have hit them hardest over the course of a lifetime’s reading.” Each person then explains its personal impact.

Aimee Bender memorized a poem as Billy Collins did. In her essay, “Light the Dark,” she says she chose “Final Soliloquy of the Interior Paramour” by Wallace Stevens (1879 – 1955). She felt elated when she had it all memorized as she was “holding all those words in my mind together.” And she realized it felt good for the body. “To feel energized by Stevens was a singular experience that reminded me how words register in our physical bodies.”

It’s Aimee’s essay that gives the book its title and the Stevens poem with its final line: “How high that highest candle lights the dark.” Of course, reading about these poems had me looking at them, and enjoying them again.

Elizabeth Gilbert writes in “In Praise of Stubborn Gladness” about discovering the poetry of Jack Gilbert (no relation to her) in 2006. Her favourite poem of Jack’s and what may be her favourite poem of all is “A Brief for the Defense.”

The world is a devastating place and as Elizabeth describes Jack’s poem, he takes the middle way rather than seeing the world as terrible or as wonderful, turning a blind eye. “Your obligation is to joy,” as Elizabeth describes it. “A real, mature, sincere joy – not a cheaply earned, ignorant joy.” In Jack’s words from the poem:

We must risk delight. We can do without pleasure,

but not delight. Not enjoyment . We must have

the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless

furnace of this world.

Apparently Jack grabbed the arm of one of his graduate students one day as she was leaving class and asked her: “Do you have the courage to be a poet? The jewels that are hiding inside you are begging you to say yes.” Elizabeth met the student when Elizabeth was teaching creative writing at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville where the visiting writer for the year before her had been Jack Gilbert.

Jack Gilbert (1934 – 2012) had the courage to be a poet. As Elizabeth describes his inspiration for all: “We need courage to take ourselves seriously, to look closely and without flinching, to regard the things that frighten us in life and art with wonder.”

In David Mitchell’s essay, “Neglect Everything Else,” he writes of James Wright’s poem “Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota.” He finds it still to be one of the most beautiful things he’s ever read.

Over my head, I see the bronze butterfly,

Asleep on the black trunk,

Blowing like a leaf in green shadow.

“Every single word is earning its place,” David says of Wright’s poem. The poem ends on a surprising note:

A chicken hawk floats over, looking for home.

I have wasted my life.

He hasn’t really though, has he? He’s written this poem. As Mitchell says: “You have to enter the hammock, put the world on hold, to really see things clearly the way the poem does.”

The title of the essay is how we get to our writing: “Neglect everything else.”

Emma Donoghue in “You and Me” writes about Emily Dickinson’s poem “Wild Nights – Wild Nights!” As a fourteen year old, in love with a girl, Emma didn’t find anyone in Irish culture in 1980s Ireland she could “see see myself in. So I used Emily Dickinson.”

Dickinson had strong passions for women in her life as well as for men, Emma says. When writing her own poems, Emma was glad to used “I” addressed to “you” as it frees one from the “necessity to specify the gender of the person you’re speaking to, so it’s a closeted lesbian’s best friend, this pronoun.”

Wild Nights – Wild Nights!

Were I with thee

Wild Nights should be

Our luxury!

We don’t know who Dickinson is addressing, in terms of gender. She’s pining for someone. It could be a woman friend as “Nineteenth-century women friends quite often addressed each other in these terms, so they didn’t draw that neat line between friendship and lover relationships the way we do.”

As Emma points out, it shouldn’t matter what a writer’s life was like or whom she was writing to, “the poem should work on its own.” But we can’t help it, can we? “There can be a wonderful tension between the life and the poems especially in poems as enigmatic as Emily Dickinson’s are.”

What has stayed with Emma Donoghue about Dickinson who “was a crucial role model” was this advice gleaned from her life: “Just follow your own passions, write your own poems. Don’t even care if they get published or not. Write them for the bliss of writing them.”

Other contributors to the book have written about novelists such as Angela Flournoy in “A Place to Call My Own” in which she writes about Zora Neale Hurston’s novel, Mules and Men. What Angela found appealing about Hurston’s fiction is: “She’s never been big on cleaning up black lives to make them seem a little more palatable to a population that’s maybe just discovering them. She’s just not interested in that.” The book is “unapologetically messy” Angela says.

Angela was in the early stages of writing her novel, The Turner House, when she read Mules and Men thinking about “working-class black people who make up 80 percent” of Detroit. She wanted to add a supernatural element to the story and started doing research on African American folklore. Hurston had done anthropological research in the South, “she went back to transcribe and collect the stories she heard growing up – as well as an account of her time as an apprentice for ‘hoodoo’ practitioners in New Orleans.”

Eileen Myles writes in “Happy Accidents” of finding Jean Stafford’s novel The Mountain Lion “at a thrift in Marfa.” I had to look up Marfa! It’s in West Texas.

I love the language Eileen uses in her descriptions of fiction. She feels that Jean Stafford (1915 – 1979) “just gets the feelings of the man, and it’s a testament to how we’re all pretty gender fluid. That’s part of what great fiction is, really: transcending gender by anyone.”

Earlier in the essay, she says: “We’re used to drag in literature, but by and large, when I read male characters written by women in conventional fiction, I still feel just this weighty burden of trying to prove that you’re in a male body and you know it.”

Eileen doesn’t read what she’s “supposed” to read including “real mass-market crap.” She needs to “read perversely. Reading is a space that is absolutely mine, that always was mine, and I’m always reclaiming it. As writers, we just need so much time to lie around, and waste time, and dream, and just be private, and flow. You can’t tell me what to think. You can’t tell me what to look at. You can’t tell me what to know.”

Eileen refers to being a kid growing up in Catholic school: “And now, when I’m supposed to be some kind of literary queer, I still want to read something else. As soon as I know who I am, I don’t want to be that person, you know?”

She found Jean Stafford’s book not even in a bookstore but rather a thrift store and Eileen likes to find books “in the wrong places.” She likes to leave books where others may find them. One book could change your life. “I love to be an agent of that. You never know what’s going to happen when you leave a book someplace.”

Neil Gaiman’s essay “Random Joy” is a great one with which to end the book. He read a book at the age of twelve or thirteen that changed the way he perceived literature. It was R. A. Lafferty’s (1914 – 2002) The Reefs of Earth, picked up in an English second hand shop. He liked the “solid chapter titles” and at some point when he went back to read the table of contents, he realized, “It’s a poem. It’s a glorious poem.” He can quote all sixteen chapter titles from memory. He includes eight of them in his essay. Here are four of them:

1. To Slay the Folks and Cleanse the Land

2. And Leave the World a Reeking Roastie

3. High Purpose of the Gallant Band

4. And Six Were Kids and One a Ghostie

I love the way these writers have described their inspiration and the late writers who are part of this continuum we’re part of. William Butler Yeats lived from 1865 to 1939 and here we are learning the words of his poem, “The Lake Isle of Innisfree,” so we can have the lines available to us at all times including in the noisy tube of an MRI. Emily Dickinson’s pronouns are useful many decades later. (She lived from 1830 to 1886.) And what good advice we have from Jack Gilbert to risk delight. And don’t R. A. Lafferty’s chapter titles entice you to write your own chapter titles that become a poem – whether you write the book or not?

There are illustrations by Doug McLean throughout the book to introduce each chapter. They include the quotations that resonate with the authors of the essays in Light the Dark.

Thank you for this, Mary Ann.

This essay is inspiring and so rich with ideas and suggestions about writers to become acquainted with.

I shall enjoy going over it in depth.

Did you know there is a documentary on W.B. Yeats on Knowledge network March 11 on the Masters series? Yeats is one of my favorite poets too.

Marlene

You’re welcome Marlene, thanks for letting me know about the W. B. Yeats documentary. I was really inspired by Light the Dark which is giving me so many ideas about how we use poetry in our day-to-day lives including those poems from the distant past. I recommend buying the book!

Thank you! This is exactly what I needed to read today, while I’m wallowing in an “overload of insignificance”. I’ll memorize a poem tonight to save myself.

And this:

“We must risk delight. We can do without pleasure,

but not delight. Not enjoyment. We must have

the stubbornness to accept our gladness in the ruthless

furnace of this world.“

(Plus I needed to kiss the pics of both William B. and Emily. Shhhh. Don’t tell anyone.)