“How did you two meet?” a participant in a poetry retreat asked Lorna Crozier when we were gathered in a lounge at a retreat centre on Vancouver Island at the end of a day of writing. Lorna had told the story of meeting Patrick Lane to those of us at the retreat the year before and yet, we were all keen to hear it again.

Quite a few of us had been studying with Patrick Lane for several years and had heard his version of the story. Mostly we had heard about the blue-jean jumpsuit Lorna was wearing on the day he met her.

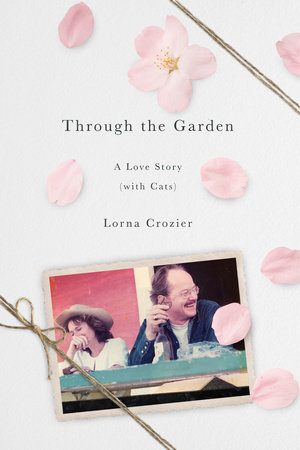

Lorna describes the meeting in her new marvelous memoir, Through the Garden: A Love Story (with Cats) (McClelland & Stewart, 2020). (Cover design: Emma Dolan.)

Lorna describes the meeting in her new marvelous memoir, Through the Garden: A Love Story (with Cats) (McClelland & Stewart, 2020). (Cover design: Emma Dolan.)

Patrick was teaching a day-long poetry workshop at the library in Regina, Saskatchewan. Lorna, at the time, was teaching high school and working as a guidance counsellor in Swift Current when she drove the three hours to Regina.

Poetry is “how I’ve made my way through the world. Line by line, heartbeat by heartbeat. It’s who I am, who Patrick is, it’s how we met,” she writes in Through the Garden which begins and ends with excerpts from Patrick’s exquisite memoir There is a Season (McClelland & Stewart, 2004) as well as a poem by Lorna, “Poem Me,” which made me weep.

Lorna was wearing her blue-jean jumpsuit when she met Patrick and “leaned forward into the force of his attention, listening to his words like someone starved of language who had just learned to read.” He was wearing jeans and a cowboy shirt with snap buttons.

About a week after the workshop, Patrick sent a note to Lorna at the high school where she was teaching saying he “regretted we hadn’t spent the night together. He said he wished he’d undone the chest-to-navel zipper on my jumpsuit,” Lorna writes. He said they’d meet again.

Two years later, in 1978, Patrick went looking for her when Lorna was teaching at Fort San in Saskatchewan where she had previously been a student. (Fort San was originally a sanitarium for patients with tuberculosis and became the Saskatchewan Summer School of the Arts in 1967.)

The woman who ran the school was “thrilled” to see Patrick Lane and gave him a room on the ground floor in the “writers’ dorm.” He didn’t use it though as he “boldly dropped his bag by my bed on the second floor,” Lorna writes.

Patrick had driven “from the Sunshine Coast through B.C. and Alberta mountains and across the prairies” to the Qu’Appelle Valley in Saskatchewan. From there, Lorna and Patrick “ran off together” leaving their respective spouses and Patrick’s two children. (He also had three children from his first marriage).

“We smashed everything to hurl ourselves into our new life. He left his wife and two little kids. I shattered my ten-year marriage, my teaching job, my master’s thesis, the good opinion of my friends and family – everything destroyed for the sake of being with this man. I knew there’d be storms, drunkenness, fights, harm; but I, a person normally full of fear, didn’t worry about the cost.” She doesn’t regret it even though, looking back, she can’t believe they had been “so daring and indiscreet.” Her memoir is a tribute to their forty years together, about thirty of them on Vancouver Island.

Lorna describes passion in her book: “I’d say to anyone who’d listen that you shouldn’t settle for a life without it, that nothing else can take its place: not friendship, security, not mutual respect. She agrees that you need “those as well” but “love without passion is tepid, and surely you want to burn.”

Those of us who have studied poetry with Patrick or Lorna know something of their passion for one another and for poetry. Patrick could zero in on what was not working in a poem and without having a printed copy in front of him, tell us the first stanza had to go or particular words could be reversed to make a startling difference. Sometimes, we got to sit with him and have him take a closer look at one of our poems, perhaps telling us a story at the same time. Now that I’m attending poetry retreats with Lorna, we’re in the same large room where Patrick, wearing his slippers, taught us.

Lorna wears her boots, sometimes the red ones, and offers so much about what is working about a poem we’ve written and brought to the circle for sharing. I’ve sometimes wondered, what is she going to find that’s good about this one and she does. She looks to the whole group as she makes her comments which then include ways of improvement, things we can think about in the next draft of the poem. There is a beautiful circle of poets, particularly on Vancouver Island, where we poets bask in the glow of having had, and continue to have, Patrick and Lorna as our teachers.

Lorna had decided on a life in poetry before she met Patrick and you can see in her prose, the wonder we’ve come to appreciate in her poetry. “[Poetry] came from and returned me to that artless kid who knelt for hours in the dirt watching a string of ants each carrying an egg like a round, white syllable to their nest under the earth, spelling something out in the loamy darkness; that kid who saw a likeness between a bluebird and a scrap of prairie sky and who felt what could only be called exaltation when she wrote across the page in a line or two what happened when her eyes met the eyes of a fox in the wild grass near the railway tracks. Boom! Crash? Shebang!”

(Photo of Lorna Crozier: Angie Abdou)

In an interview with Robin Dyke for the Victoria Writers’ Festival, Lorna said she started the writing for Through the Garden in 2017. (The first date noted in the book is February, 2017.) As Lorna and Patrick both worried about his illness and what may be causing it, “the only thing I could think to do was to go into my office and try to write because that’s how I’ve lived my life, I’ve written my way through pain and sorrow and joy into a space that holds some consolation, although I don’t know if I’m there yet,” she said.

Patrick was nine years older than Lorna so she realized that “in all likelihood I was going to be the one left alone.” And she said: “It’s as bad as I thought it would be.”

The structure of the book works so well with various dates throughout Patrick’s illness, non-chronological reflections, and the integration of poetry throughout the beautiful prose. The timing of revealing how they met isn’t told until the middle of the book. The process Lorna said was organic. “I would write a sentence or a few sentences and then I would go back and I would revise them until I felt the cadence was right, I’d try for the best adjective I could find, got rid of any clichés and then I would move on . . . the process, including the order, was intuitive.”

The book is as heartbreaking as only the continued deterioration of a beloved’s health and well-being can be.

The hospital bed Lorna snuggles in with Patrick, “among the tubes and monitors that register his blood pressure, heart rate, oxygen level” is “the same size as the one where we spent our first nights together when Patrick moved into my room at the Summer School of the Arts in the old TB sanitarium in Fort Qu-Appelle,” Lorna writes.

And there’s humour too. Lorna says she’s sorry about the division of labour; she and Patrick should have “split the same tasks, not delegated one thing to me and another to him.” There are various things she doesn’t know how to do such as setting the timer for the irrigation system in the garden. It’s all very frustrating and she feels she wants to kick a hole in the wall. “But then who would fix it?”

Lorna has spoken about writing and risk at her Ralph Gustafson Distinguished Poet lecture at Vancouver Island University. She took a risk in her memoir in describing the early days of living with Patrick in Winnipeg when they had a a visit from a couple of poets, two friends of Patrick’s from Vancouver Island. Lorna calls them Rick and Cathy. Before the two arrived, Patrick “confessed that he’d slept with Cathy” a few months before, just before he left B.C. for Saskatchewan to find Lorna.

I say risk because Lorna risks that we won’t like her behaviour, maybe not like her, but in fact her behaviour is so like our own if we just admit it. “Although I swore that I’d try to like her, I was pleased to see that Cathy, a short woman with a pretty face, was chubby, and the pale blond hair that grazed her shoulders looked as dry as wheat stubble in a fallow field.” Although Lorna “felt guilty noting things like that,” she couldn’t stop herself. There’s more to that occasion that I’ll leave for you to read as it reveals a surprising bit of the paranormal. I’ve observed psychokinesis but this is a bit different!

Twenty-one years ago Lorna went to her first Al-Anon meeting admitting Patrick was an alcoholic before he began recovery, attending a six-week drug and alcohol rehabilitation centre. Once he had gone six months without a drink, he proposed to Lorna. “He wanted to make a new commitment to me,” Lorna writes. “We lived together for twenty-three years before we got married in the back garden of our former house in Saanichton, the setting for Patrick’s memoir and our home for fifteen years.”

Their love affair “built on poetry and lust” lasted over forty years. “Who knew there’d be time or space for domestic complacency, addiction, a devastating illness, a durable abiding respect and affection, the common banality of a man and woman living together year after year after year, a garden, a house, cat and a cat and a cat.”

The cats were Nowlan, Dickens, Roxy, Basho and Po-Chu I and among the many poems Lorna includes in the book is a previously unpublished one: “The Cat we Called Basho (d. Nov. 17, 2018, 8:05 a.m.)

Patrick was in the hospital when Lorna had to have 18-year-old Basho, put down. I know the soul connection one has with a cat, each with their own distinct personality, each with no grudge to bear. Patrick’s son Michael helped Lorna bury Basho. “There’s no way to prepare yourself for the sound and sight of earth falling on a body. It is your naked heart lying there, the dirt landing hard and cold,” Lorna writes.

While the bed had been Basho’s territory, it was Po who curled beside Lorna on the bed the morning Basho died. Po doesn’t meow. “The sound she makes to get attention is a cross between a whimper and a squeak.” She was in rough shape when they brought her home and getting near her meant hissing and the slashing of Lorna and Patrick’s arms and legs. Patrick said: “She’s just scared. I’ll work on her. You stay out of it.”

“We aspired to flourish together and thrive in words and books and gardens,” Lorna writes and that’s what they did. In an interview Lorna did with Marsha Lederman of the Globe and Mail (Saturday, September 12, 2020), Marsha asked Lorna how Po is doing. Since Patrick died, Po has gone up to Lorna in the gazebo making her squeaky sound. “And I finally figured out she wanted me to lie down with her. So I walked to the bedroom, she’d trot ahead of me, jump on the bed. I would lie down and she’d curl up beside me and purr. It was almost like a rescue mission.”

The Globe article is entitled “What happens when the love story ends?” The love story has not ended. While Patrick may not be on this earth in physical form, his spirit lives on in so many ways, with so many people who feel privileged by his poetry and his teaching, and especially in the garden he shared with Lorna. That’s where Po is on her rescue mission. I’m sure Patrick had something to do with that.

(Photo of Lorna Crozier and Patrick Lane: Rafal Gerszak/The Globe and Mail)

Thanks for this piece, Mary Ann — it propelled me to google’s preview of the book, and then straight to amazon to add ‘Through the Garden: A Love Story (with Cats)’ to my wishlist.

If you order from Munro’s in Victoria, I think you’d get a copy autographed by Lorna!

Wow, the heat of their passion comes through your wordd, even though you’ve not written anything at all “untoward”!! I imagine it’s difficult to disguise it, given the pretty radical losses and choices!

And sometimes it works, which it obviously did for these two. How lucky that your path crossed theirs, and your poetry received their benedictions!

Thank you Mary Ann for a beautiful and thorough review. Anyone who has studied with them, anyone who knows their poetry and writing, anyone who loves a love story, in fact, the whole world will love this book.