Lori Fox, based in Whitehorse, Yukon, describes their new book of essays, This Has Always Been a War (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2021), as a “scrappy, angry little book” with its sub-title of “The Radicalization of a Working-Class Queer.”

In an interview with Yukon News for which she has been a writer, Lori said: “The book is incredibly vulnerable. I’m incredibly blunt, and really upfront with some very difficult things. And I pull no punches.”

Indeed, there is much to be angry about as Lori describes in their wonderfully written, often visceral, essays. The essays describe their confrontations “with the capitalist patriarchy through their experiences as a queer, non-binary, working-class farmhand, labourer, bartender, bushworker, and road dog . . .” As the book’s cover description says: “Capitalism has infiltrated every aspect of our personal, social, economic, and sexual lives.”

It is their work as a journalist that led me to Lori’s book as I’ve very much appreciated their opinion pieces in The Globe and Mail.

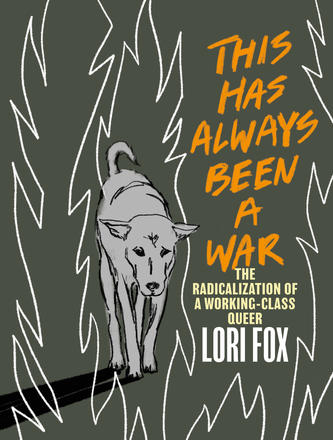

The dog on the cover, designed by Jazmin Welch, probably represents Herman who has been by Lori’s side through many hardships and adventures, at lean times sharing a meal of ramen noodles.

This Has Always Been a War is, Lori says, “for my people, the working classes, who cook the meals and pick the fruit, who serve the tables and stock the shelves, who work the gigs and deliver the orders. We are the makers and builders and doers of this world, and all that is in it belongs to us.”

This Has Always Been a War is, Lori says, “for my people, the working classes, who cook the meals and pick the fruit, who serve the tables and stock the shelves, who work the gigs and deliver the orders. We are the makers and builders and doers of this world, and all that is in it belongs to us.”

If you don’t already consider the wait staff in the restaurant you visit, or the people who have picked the fruit that you buy at your local grocery store or any number of people who “serve” us, you will have your eyes open to the indignities suffered, the abuse meted out by those in power, and the deplorable conditions people work under when you read this book. Lori Fox has experienced it all first hand.

Lori fights back in the very writing of this book and when they’re able, to physically retaliates. In “At Your Service,” the first essay in the book, Lori is working in an Ottawa pub where a male customer sexually assaults them. Lori upends a pitcher of sixty ounces of cold Molson Canadian over him. Good for you Lori Fox, I said to myself.

The customer who was escorted off the premises, called in the next day “to complain about the quality of service he’d received.” Thankfully, Lori had “hands down the best boss I’ve ever had,” who hung up on the “groper.”

Lori reflects: “As a consumer, he [the customer] felt entitled not only to my service, but to look at, even touch the body committed to that service, because my body (or, at the very least, my feminine attention) was viewed as part of what he’d paid for when he bought that pitcher of Canadian lager.”

From 2003 to 2020, Lori “was employed, more or less continuously in family diners, nightclubs, fine dining establishments, greasy spoons, blue-collar dives” and a whisky bar.

“Capitalism is not simply an economic system, capitalism is culture. Specifically, capitalism is our culture. And under capitalism – within our culture – working-class bodies are property,” Lori writes.

“Feeding people, giving people good food and good drink and a place to sit and talk and laugh, or a place to be alone and have someone take care of them so they can just enjoy and think, is a genuinely beautiful thing,” Lori writes. They note other beautiful things and says: “there are also people who work really, really hard and still don’t have enough to pay the rent and buy groceries.” There are people who can’t afford to take a day off to go to the doctor when they’re sick or go to the dentist because they can’t afford it.

Capitalism is “a system of learned helplessness,” Lori writes. “And it doesn’t have to be this way.”

In “The Happy Family Game,” Lori describes their home life which was a frightening place to be.

“The objective of the Happy Family Game is to create a nuclear family unit which, either in reality or in appearance, looks to outside eyes to be ‘successful in every way including’ doing their moral duty to purchase and enjoy the products and services that capitalism creates.”

When Lori, at twelve years of age, told their mother that their mother’s father had raped them, Lori was told not to tell anyone as if getting their grandfather in “trouble” and “tearing the family apart” would be their responsibility.

“In the Happy Family Game, men are the only players who matter,” Lori writes.

The silence for many who have suffered trauma is worse than the event or assault, in this case, itself. Lori says the event was not spoken of again and they were “made to continue behaving as if nothing had happened.” The family was protected at a child’s expense.

Growing up also meant living with a raging father who she writes about in “Every Little Act of Cruelty.” Lori describes living with him was “like living with a toddler – a 180-pound toddler in charge of the chequebook, with access to firearms.” Following his meltdowns or rages, “in other words, completely insane,” it was if they didn’t happen.

Lori writes: “as an adult and a transmasculine person, someone who occupies the vast and wild country in between man and woman, I am also terribly afraid of becoming him. Of becoming a man like him.” They have inherited physical similarities and other “less tangible traits.” Those intangible traits are: “A tendency toward depression. Chronic, near-crippling anxiety. Panic attacks. Dissociation. Suicidal ideation. Hypervigilance.”

Lori and their brother were kept away from other children, neither visiting them or having them over. Questions could “lead someone to discover the severity of my father’s illness – and his abusive behavior. All this secrecy and misery, all this abuse and suffering, and loneliness, was allowed to continue with one thought in mind: to protect my father, not from himself, which actually would have been useful, but from losing face in the eyes of the world.”

Lori, as a writer, a journalist, as someone who has lived experience as well as information gathered through their own investigative research, wonders why.

“Because my father was a straight white man in a straight white neighbourhood where you did not question the things straight white men did in their homes. A king in his castle. Capitalism needs patriarchy – specifically, it needs a family man headed by a patriarch.”

Lori shares “several truths” about their father including being “a deeply unwell man,” “an unhinged, unstable, misogynistic, violent prick who was a threat to himself and to others,” as well as a “family man who tried his best to provide for his family” and a man “disappointed that his life didn’t turn out the way he’d thought it would.”

I’ve read several memoirs and the horrible conditions people have grown up in makes me wonder how they ever made it to adulthood. One way of surviving as an adult, is to write about what happened, creating a bridge between then and now, putting an end to silence.

Sue William Silverman, author of Because I remember Terror, Father, I Remember You, said about her own memoir writing: “I could hold this book, this tangible thing. And it takes it out of you. It’s like writing that pressure out of the pressure cooker. Each word that comes out is like taking a little piece of pain with it and putting it on the page. Which isn’t to say that you don’t still have feeling about it. Of course you do. But it just takes away a lot of that power it has over you, and you feel a kind of distance towards it.” (from Writing Hard Stories: Celebrated Memoirists Who Shaped Art from Trauma by Melanie Brooks)

Lori writes about dystopian novels in their essay “Where the Fuck Are We in Your Dystopia?” Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale is included among the ten titles Lori read or primarily consumed as audiobooks, most of them written in the last five years. (They also read Atwood’s The Testaments.)

Lori writes about dystopian novels in their essay “Where the Fuck Are We in Your Dystopia?” Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale is included among the ten titles Lori read or primarily consumed as audiobooks, most of them written in the last five years. (They also read Atwood’s The Testaments.)

In one hundred hours of words, “queer people are almost entirely absent.” The works are described as “feminist dystopian fiction” and Lori asks: “For whom is the ‘feminism’ it depicts? How can you have feminism without queer women and non-binary people?” Which leads to the question raised in the title of the essay.

Also, “What is missing, largely, is people of colour and working-class people.”

Lori calls Atwood “a champagne feminist” at best and votes for “the more talented and good-hearted Alice Munro to usurp Atwood as Canada’s Literary Queen.”

The longest essay in the book is “Call You by Your Name” about a relationship Lori had with a man that was complicated, hurtful and as it turned out, abusive. Lori had quit her job and “disappeared into the bush with my truck and camper” after her lover Gabrielle left them.

In an earlier essay referring to the relationship with the man she calls Lucky, “The Hour You Are Most Alone,” (published previously in The Guardian), Lori writes:” I began a relationship with a man who quickly took what little control I had left. Charming and manipulative, he threatened and abused me physically and emotionally, assuming control of my money, curating where I went and who I spoke to. When I had the strength to protest, he battered me down.”

In “Call You By Your Name,” Lori addresses as “you.” I can’t help but see Lori’s situation with the manipulative man as a microcosm of their life in a “capitalist patriarchy.” Even when reaching out for some help to two men in business suits at Whistler, B.c. where Lori was living in her camper and working construction, offered nothing. Lori had been raped by her boyfriend and wondered if the men knew of any hotel rooms that weren’t too expensive. They suggested going home and one said: “ . . . my boyfriend was probably worried about me.”

This is the essay that is visceral and graphic in its descriptions of the abuse meted out and Lori’s physical reactions.

The essay that gives the book its title, “This Has Always Been a War,” is about Lori’s work at a vineyard in Naramata, B.C. where their job was “thinning.” There are several wineries in Naramata on Okanagan Lake “where the houses of the wealthy popped up all in a line on either side of the road, like fairy ring mushrooms.”

At the vineyard, workers “were not to use the indoor washrooms, which had running water, but the green porta johns . . . “. It was financially impossible for workers to live in the village. Earlier in the season, Lori had worked picking cherries for a farm where there was a bunkhouse. The workers who had camped in tents were gone and the farmer offered to let Lori stay on. The bunkhouse had a stove and a fridge but no bathroom. Workers used “porta johns” but they were gone as the workers were gone. Lori used a “President’s Choice Dark Roast coffee tin.”

While hired to do garden work to supplement their meager income, Lori was invited into the house only once by the wife “of a ridiculously wealthy older man who owned several wineries in the area” to use the washroom.

One day, when her employer and her guests were seated outside at a table drinking wine, she spoke to Lori. All kept their distance not offering Lori anything to drink in the heat. One of the women acknowledged it was difficult for workers to find a place to live. Lori said she lived in a tent on one of the farms and before that on a logging road in her truck.

“There needs to be a communal camp for all the workers, so we’d have running water and showers and a place to sleep and cook,” Lori said. Her employer waved her one hand “as if brushing the idea away.”

Lori’s employer said: “Where would we put it that it wouldn’t be in the way? It’s also far too expensive – and the government won’t give us any money for it. We can’t be expected to pay for it ourselves.” That sort of comment makes we want to spit!

As we eat cherries from the Okanagan and drink wine from the same area of B.C., let’s be aware of what it took to get those items to us.

When Lori was last working in Naramata in 2018, they “thought about how it was that a handful of people could have everything, while so many people did not have enough, or anything at all.” The workers in the fields, picking the fruit and cutting the vines, “grew food they didn’t get to eat and made wine they didn’t get to drink.”

There are several paragraphs beginning with “what if” including: “What if working-class people just stopped working?”

“To free ourselves from capitalism might mean violence, but that violence would be – is – self-defence.

“I’m not calling for war. This already a war.

“This has always been a war.”

Great review Mary Ann.

Thanks for this review Mary Anne. I’m not sure I would have read Lori’s book if I hadn’t first been introduced to it through your review – which is a great introduction. I so appreciate what Lori has addressed with such an honest narrative. I am grateful for their courage and for the decision they made (after reading ‘The Jungle Book’) , and they describe at the end of their book. I appreciate the honouring inherent in your review of Lori’s words and value your acknowledgement that one way of surviving and to put an end to silence is to write about what happened. The space you provide for just that, through the writing circles you offer, creates opportunity for more voices to be heard.

Thank you Kate for taking the time to write your thoughts about This Has Always Been a War, my blog and the writing circles too.