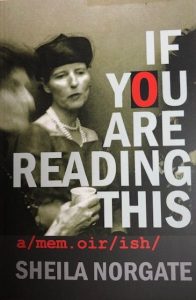

If You are Reading This is Sheila Norgate’s a/mem.oir/ish, a book of personal essays published under her own imprint: LIP (Ladies Institute Press).

As Sheila told me in a phone conversation, she’s a “one girl band” having written the book, designed it (including the amazing cover) and published it. I’ve always thought writing to be one of the healing arts and taking one’s story and putting it into the world is all part of that healing. Sheila agrees, that it’s especially important for women to put our words into the world.

Readers will have their own endings to “If You Are Reading This” which could be similar to my responses: “be forewarned;” “be prepared to laugh;” “expect to be shocked and amazed,” and “you’ll have your socks knocked off.”

Sheila’s memoir includes all that a feminist memoir ought to. She lets us know what happened in her life, how she felt about it and she has observed and researched the bigger picture that has affected her and in fact, all women.

If You Are Reading This reads on the page as Sheila sounds in her performances, sharing her stories from life with humour and gravitas. She has given one-woman performances for many years, doing the writing, producing and presenting to enthusiastic audiences. I’m grateful I was able to attend several of them on Gabriola Island, B.C. where she lives with her partner Debbie, as well as in Victoria and Nanaimo.

If You Are Reading This reads on the page as Sheila sounds in her performances, sharing her stories from life with humour and gravitas. She has given one-woman performances for many years, doing the writing, producing and presenting to enthusiastic audiences. I’m grateful I was able to attend several of them on Gabriola Island, B.C. where she lives with her partner Debbie, as well as in Victoria and Nanaimo.

Sheila told me she wouldn’t be performing if she hadn’t moved to Gabriola in 1999. Besides Gabriolans being a fabulous audience, publicizing an event and renting a hall is much more inexpensive than it would be in Toronto or Vancouver.

Sheila has also done much research into issues concerning women including the “advice” we’ve been given through the years. That advice is entertaining as well as horrifying. Sheila has a collection of etiquette books published between 1930 and 1960 that have provided her with evidence that women have been continually told how to “slim, trim, pin down, curb [and] limit.”

Also a visual artist, Sheila says in the introduction to her book that her memoir was “stowed away for 30 years in my visual art practice.” The memoir “started to bleed out” into her paintings to which she gave titles in the early years (1980s). Text made its way onto the canvas in the form of penciled handwriting and later with alphabet stamps. So they would be large enough, Sheila carved her own stamps out of rubber.

While Sheila may have lost patrons due to the “predilection,” for words, she figures that’s none of her business. “The business of any artist is to take direction from her muses, not her shifting fanbase.”

One of her essays, “On Being a Lady Painter,” describes Sheila’s journey as a visual artist with illustrations of her work.

It takes courage, and some outrageousness, to stand up and tell one’s life story to an audience. The challenge for Sheila was committing her memoir to “hardcopy.” She figures performances are more “transitory” whereas writing can be referred to again.

She’s done it, taken on the printed page, and her wings are now spread wide to include performance, visual art and published writing.

In “Lesbian Nightowls & Other Oxymorons,” Sheila says lesbians “can’t seem to remain conscious past 9:30 p.m.” As for “lesbian bed death,” a phrase coined by a sociologist in 1983, Sheila has done some investigating. Two women may have less sex than other couples (straight or gay men) because there is the likelihood one or both have experienced sexual violence. (One in four women in Canada have or will experience sexual violence.)

Sheila notes internalized homophobia too for “no matter how liberal and inclusive” people are, it falls “to us (the queer folks) to deal with our internationalized homophobia.”

I’m thinking lesbians have more in common with one another than with male partners and they may have expended most of their energy on those shared passions until 9:30 p.m. You can see there is much to discuss at the next lesbian potluck.

When writing about “The (Not So) Great Out-Doors,” Sheila thinks “there’s always a predator out there. It isn’t lost on me that the predators from my childhood were in fact, my parents, and they operated almost exclusively indoors.”

And yet Sheila felt she had more control indoors “simply because the jurisdiction of my worry is so much smaller when compared with the outdoors.”

Sheila’s “early holding environment” was not even close to “good enough” and if it was for you, says: “It won’t likely occur to you to take up psychotherapy on a permanent basis, or routinely daydream about suicide, or swap out intimate relationships like snow tires, or volunteer for a phone-in crisis line only to have to make your own desperate late-night call a few months later. These are all things I have done.”

Before she could form full sentences, Sheila would have to answer Einstein’s question about whether the world is a friendly place with the word “no.”

Her beloved small maltese-poodle named Rosie adopted in 2001 gave Sheila unconditional love that lasted seventeen years. Among the paintings of dogs Sheila did, one of her favourites was “first responder.” Rosie offered Sheila “the power of secure, uncontaminated love,” cheering her on.

In an essay entitled “Always Becoming Never Quite There,” Sheila describes the collection of etiquette books I mentioned earlier. She has 127 of them that include “charm manuals, beauty guides, sewing handouts, and home economics texts.”

In an essay entitled “Always Becoming Never Quite There,” Sheila describes the collection of etiquette books I mentioned earlier. She has 127 of them that include “charm manuals, beauty guides, sewing handouts, and home economics texts.”

Sheila wasn’t “particularly shocked to read that it’s not good form for a woman to stop at a motel without luggage.” What she “wasn’t prepared to exhume, was the cover-to-cover counsel littering these books about how to “control, contain, restrain” and many other words to that effect to “generally correct the female body.”

Sheila writes: “And we might just want to ask who benefits from the campaign to divert women and girls from the real work of our lives; to be fully embodied, to be fully engaged, to be steeped in our voices.”

A beautiful manifesto for women, I think.

“MelancholyBaby” begins with humour: “On the night I was born, my mother was at home, and my father – an amateur spiritualist – was at a seance.”

Uncle Paul, with his 1946 Buick sedan, was contacted by Sheila’s mother who was at home and going into labour. He “retrieved” Dad from the seance and they headed for the hospital. It was February 7, 1950 and “somewhere near the busy intersection of Queen Street and Broadview Avenue in Toronto” Sheila’s mother, in the back seat with Dad, “succumbed to the physiological imperative.”

Sheila describes what a birth in the hospital would have been like for women in 1950 flat on their backs, sedated against their will and other horrors.

Sheila and her mother didn’t make it to the hospital for the birth and they were separated when they got there. They didn’t see one other for several days.

“Some 30 years later, my mother admitted that she hadn’t been able to bond with me. It was shortly after this conversation, that I engaged the first in a long, protracted motorcade of therapists.”

Sheila writes of having rosacea and Raynaud’s disease which causes fingers and toes to go white and numb. In a chapter titled “Little Pigs Have Long Ears,” she describes having otoplasty at the age of eight which “refers to a genus of plastic surgery procedures designed to correct anomalies of the external ear.”

Sheila’s ears still hurt if she lies on either of them for an extended period of time. The one thing that saw her through the time in the hospital following surgery (her mother’s decision), was the fact she made the nurses laugh.

As with other memoirs in which women tell their stories from life, Sheila writes of what happened in her early life and how it affected her and shaped her. She’s been a “seeker” all her life she told me and has read extensively, especially books about how to be “less fucked up.”

The main thrust of that seeking, she said, has been to see what makes her tick and how to manage in this world.

Much of Sheila’s learning was done through psychotherapy as she went into therapy in 1981. She remembers back to the time she took two years of a general arts degree at the University of Toronto and “psych” or “soc” were part of the title of every course she took.

Sheila writes of her parents, her mother, an English “war bride” from England and her father, a Canadian serviceman, in “Pier 21” where her mother would have entered Canada via Halifax.

“In Seriously Funny Girl,” Sheila writes of being funny all her life. While still in school, as she reflects in her essay on the humour related to her slow developing breasts, she writes: “Back then, I was unaware of the role that self-effacement played in my life, but I see now that it was a pre-emptive strike of sorts. A comedic confessional where nobody could get anything on me that I hadn’t already gotten on myself.”

The chapter entitled “God and I Are Like This” took the longest to write she told me. It’s the final chapter in which there is so much to which I can relate: going to Sunday School, finding “second-wave feminism in the back room of the Toronto Women’s Bookstore” and having Alister Crowley tarots cards among her belongings. Sheila writes of finding love, losing it for a time, and finding it again.

The chapter entitled “God and I Are Like This” took the longest to write she told me. It’s the final chapter in which there is so much to which I can relate: going to Sunday School, finding “second-wave feminism in the back room of the Toronto Women’s Bookstore” and having Alister Crowley tarots cards among her belongings. Sheila writes of finding love, losing it for a time, and finding it again.

There’s lots more to Sheila’s story that you’ll have to read for yourself including her powerful and poignant last sentence which has come after much investigation, reflection and self-compassion. Although there’s a sense of happily ever after, there is also the fact that there is much in the world to rant about. I expect Sheila will be doing more of that.

To order a copy of If You Are Reading This, visit Sheila’s website where you can hear her read small portions from her book.

If you are in Nanaimo or surrounding area, Sheila will be reading from If You Are Reading This at the downtown Nanaimo branch of the Vancouver Island Regional Library on Saturday, June 25th from 2:30 to 3:30 p.m. See further info here.

Oh my gosh! Sheila Norgate! I first became acquainted with her work way back in the ’90s when I saw an exhibit of her visual art on Granville Island. I was absolutely wowed by it and have wondered what ever happened to her. I’m so delighted to read this and will look forward to the book!

Sheila Norgates’s YouTube shorts have been a main stay of pandemic viewing for me. Sheila is funny, provocative and insightful. Thanks for this great review Mary Ann. I look forward to hearing Sheila share her book and to having my own copy!

This is too funny, Mary Ann – I have literally wandered through the internet and happened upon you! So glad I did. Briefly, the crooked path wound its way from the Deep Transformation network, to a link re. ecoliteracy, to the book The Wander Society, to you. Wandering all the way.

I’m a former teacher, now writer, living in Victoria, wandering my way into writing a spiritual memoir on re(story)ing human nature in a world filled with sentience – or something to that effect.

I’ll read more of your posts and thank you for the recommendation of If You are Reading This.

All Best.

Val

I’m glad you found me Val! Victoria is a wonderful place to be for many reasons including having a vibrant writing community. Perhaps we’ll meet in person at a literary event. I like the sound of your spiritual memoir. Wondering does offer many rewards.