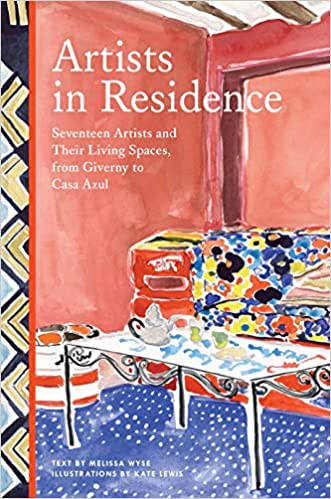

Artists in Residence (Chronicle Books, 2021) is a book that features the homes of seventeen artists “and their living spaces, from Giverny to Casa Azul.” I really appreciate Melissa Wyse’s writing with her enthusiasm for and fresh approach to her subjects. And the illustrations by Kate Lewis are delightful and enticing.

Melissa Wyse is an art writer, fiction writer, and essayist who lives in Brooklyn, New York. Kate Lewis is an artist whose paintings are in private collections around the world. She lives in Chicago. The two met in the summer of 2017 at the Ragdale Foundation and their continued connection, some serendipity, and a “strange alchemy” led to this engaging book. Melissa and Kate encourage readers to follow their own curiosities.

As their introduction says, “Some of the artists in this book used their homes as places where they explored materials, staged still lifes, or inhabited the aesthetic vocabularies that would inform their artistic production. Others experienced their homes as sites of divergence, places where they stepped away from the hallmarks of their artistic work to embrace radically different colors, patterns, or aesthetic experiences.”

I do love that term “aesthetic vocabularies”!

Georgia O’Keeffe is the first artist in the book. Her home, in the village of Abiquiu, New Mexico, is open to the public. I’ve seen the outside of O’Keeffe’s adobe house but hadn’t booked a tour which has to be done many months in advance. The illustration shown is of “a weathered wooden door” that leads into O’Keeffe’s living room. ”

Georgia O’Keeffe is the first artist in the book. Her home, in the village of Abiquiu, New Mexico, is open to the public. I’ve seen the outside of O’Keeffe’s adobe house but hadn’t booked a tour which has to be done many months in advance. The illustration shown is of “a weathered wooden door” that leads into O’Keeffe’s living room. ”

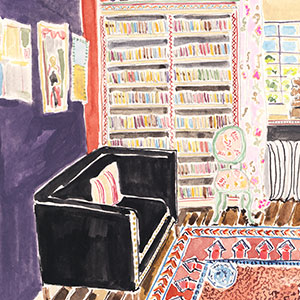

Louise Bourgeois was born in Paris in 1911 and moved to New York City in 1938. “She worked as an artist for over seven decades, right until her death in 2010 at the age of ninety-eight.”

Bourgeois’ townhouse on West 20th Street was cluttered with stacks of paper, photos and articles pinned to the wall and English and French phrases as well as phone numbers written above her mantel. I appreciate Melissa’s take on the clutter:

“In our culture, with its stigmas against clutter and holding on to too much, we ignore the generative capacity of collecting and stacking up, all the pain and protection accumulation can hold. It can become a fortressing that keeps us safe – and a repository. All those books and papers allowed Bourgeois to live encompassed by the material traces of the past. Her archiving connected her with the seeds of memory that were such essential sources for her art.”

After her husband died in 1962 and after their three sons had grown, Bourgeois rearranged the rooms in her house, expanding her basement studio space into the ground floor living spaces. On Sundays she would open her home and host salons attended by various members of the community and especially “younger, emerging artists.”

Many of the homes described in the book have been preserved and the Louise Bourgeois home is one of them, by the Easton Foundation.

Many of the homes described in the book have been preserved and the Louise Bourgeois home is one of them, by the Easton Foundation.

The cover of the book, on the left, has an illustration of Hassan Hajjaj’s home in Marrakech, Morocco which serves as his private home and studio: Riad Yima where there is also a tearoom and boutique.

Clementine Hunter’s house on the Melrose Plantation in Louisiana is preserved by the Association for the Preservation of Historic Natchitoches.

Hunter’s home was owned by her employer for whom she worked as a servant in the plantation house starting when she was fifty years old. Before that, she had worked for decades as a field hand. She salvaged leftover paints from the artists who stayed at Melrose, painting scenes from life on the plantation and the surrounding community.

Her work was exhibited in gallery shows and Hunter “often sold her paintings herself from her home’s screened front porch.” In 1977, the Melrose Plantation was sold and the Cane River flooded, “sending water under Hunter’s house.” She moved into a house trailer at the age of ninety.

The old tin-roofed cabin was moved to the heart of the plantation grounds where it has been preserved and visitors can take a tour. The whole house hasn’t been preserved though. As Melissa points out, it’s “strangely pulled apart; the kitchen and the bathroom shorn off the back of the building, the wall paper removed, the linoleum peeled off , the house stripped down to its floorboards and wood wall planks.”

Melissa goes on to say about the preservation: “It blurs the temporal realities of her life and denies the specifics of her experience . . . In an area dotted with restored plantation houses, in a country that continues to enact its racism in overt and subtle ways, Hunter’s stripped-down house feels symptomatic of a larger problem in how we tell and what we omit from history.”

Clementine Hunter would wallpaper her walls and onto the ceiling. Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant, at their home in Charleston, East Sussex, England, painted on all its surfaces including walls, mantels, doors and doorframes, and furniture.

If you’ve read about Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf’s sister, you may know she was married to art critic Clive Bell and they had two sons, Julian and Quentin. The couple had an “open marriage” with Clive moving into the Charleston house (with Vanessa and Duncan Grant) in 1939, living in his own “suite of rooms.”

If you’ve read about Vanessa Bell, Virginia Woolf’s sister, you may know she was married to art critic Clive Bell and they had two sons, Julian and Quentin. The couple had an “open marriage” with Clive moving into the Charleston house (with Vanessa and Duncan Grant) in 1939, living in his own “suite of rooms.”

Duncan Grant had several romantic relationships with men and with Vanessa Bell with whom he had a daughter Angelica in 1918. After their physical relationship ended, Bell and Grant remained close friends and lived together for most of their lives. “At Charleston, they enjoyed a harmonious and egalitarian approach to domestic living.”

As directors of Omega, an artists’ design collective, Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant “crafted a philosophical framework that informed their approach to their own home at Charleston. They saw their rigorous practice of painting their home’s surfaces as a part of, and equal to, their artistic expression elsewhere . . . at Omega they had asserted the idea that decorative arts and interior decoration possessed intrinsic artistic value. In keeping with this philosophy, they transformed Charleston into a house-sized painting, a piece of art in its own right.”

Theirs was not a “traditional domestic experience” and Bell and Grant “painted an entirely new way to experience the space of home.”

And wouldn’t it be good if we aspired to the qualities Melissa describes of the Bell-Grant home, in our own homes: ““The inventiveness of their interior decoration mirrored the environment they fostered for the people within it: one that embraced tolerance, open-mindedness, creative and intellectual engagement, and personal freedom.”

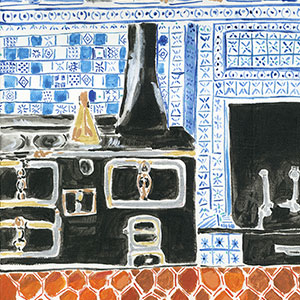

Claude Monet’s house in Giverny, France is wild Melissa says. “Each room is an experiment in color, an invitation to the limits of how saturation shapes space.”

Claude Monet’s house in Giverny, France is wild Melissa says. “Each room is an experiment in color, an invitation to the limits of how saturation shapes space.”

One of the illustrations in the Claude Monet chapter of the book is the yellow dining room where nearly everything is painted yellow. “Yellow even checkers the brightly tiled floor.” The illustration to the left is of the “enormous oven” in the kitchen where the walls are blue and tiled “with a constellation of organic blue and white starbursts and fleur-de-lis patterns.”

“When I think about Monet’s house at Giverny,” Melissa writes, “I think about how it feels to be submerged in color and space. His home aligns with my sense that aesthetic choices can be not just decorative, but also experiential, and that our experience of interior spaces can shape the way we feel. And while Monet’s interiors didn’t adopt his art’s content or style they do share his heightened awareness of color’s impact . . . In his home, he stepped easily between two worlds: the gardens that served as his core artistic subject and inspiration and the centering aesthetic experience of his house’s interiors.”

If I ever travel to Mexico City, I’ll certainly want to see the homes of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. There is the Kahlo home, Casa Azul, in Coyoacan, on the outskirts of Mexico City, and the two adjoining houses Rivera had built for himself and Kahlo in the San Angel neighbourhood of Mexico City.

“As her physical health worsened, Kahlo’s home became even more important for her as a source of creative stimulation and engagement,“ Melissa writes. The kitchen at Casa Azul has yellow floors and table with the lower portion of the walls painted bright blue. Most of the kitchenware is visible along with wooden spoons on the wall and painted pottery dishes on open shelves.

“Kahlo’s home feels like a distinct work of art, separate from her paintings. It has its own vocabulary of shape and form, color and line, its own aesthetic preoccupations and interests. It serves its own purpose, not as a staging ground or sketch or backdrop for her art.”

Vincent van Gogh, a Dutch painter, in May 1889, “voluntarily admitted himself to Saint Paul de Mausole, a psychiatric asylum in Saint-Remy, France. His former home in Arles, France and his room at the Saint-Remy asylum “served as places in which to paint and also as subjects of his paintings.”

Melissa says of Van Gogh: “He did not create his art in the thrall of mental illness; during and immediately after episodes, he was unable to create at all. He created his immense body of work through the diligent daily painting practice he adopted during the lucid months between attacks, when he saw his creative work as a way to maintain his sanity, to save his mind, to keep some traction on his own well-being.”

Other artists in the collection include Donald Judd, Claude Monet, Less Krasner & Jackson Pollock, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Zaria Forman and Henri Matisse.

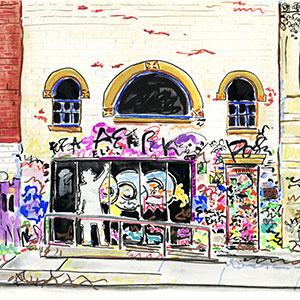

It’s touching to read of Jean-Michel Basquiat, born in Brooklyn in 1960 to a Haitian father and a mother of Puerto Rican descent. He had a loft on Crosby Street and then a two-storey building at 57 Jones Street in New York’s SoHo. He died at the age of twenty-seven at the Jones Street location in 1988. The illustrations in the chapter are of suits, bicycles, audio and video cassettes. “He had always been interested in the creative potential of objects, from his teenage days of making assemblages from found objects on the street,” Melissa says.

It’s touching to read of Jean-Michel Basquiat, born in Brooklyn in 1960 to a Haitian father and a mother of Puerto Rican descent. He had a loft on Crosby Street and then a two-storey building at 57 Jones Street in New York’s SoHo. He died at the age of twenty-seven at the Jones Street location in 1988. The illustrations in the chapter are of suits, bicycles, audio and video cassettes. “He had always been interested in the creative potential of objects, from his teenage days of making assemblages from found objects on the street,” Melissa says.

Visitors are not able to visit Basquiat’s former home but admirers do travel on pilgrimages to 57 Great Jones Street and have left graffiti on the outside of the building. “It is an evolving, unofficial exhibit – the outside walls of his home transmuted into a living site of art.” There is also a plaque for Basquiat installed by the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation.

“Sometimes houses are preserved. Sometimes they endure,” Melissa says.

I can understand how Melissa Wyse and Kate Lewis felt a “new intimacy with the creative life of each artist” as they visited, painted, wrote about, imagined the homes of the visual artists included in Artists in Residence. Readers get to experience that too. I think we’re always fascinated to see where artists and writers create their work, how their homes influenced and supported their work and how their homes so often were and are living works of art.

Excerpted from Artists in Residence: Seventeen Artists and Their Living Spaces, from Giverny to Casa Azul Hardcover © 2021 by author Melissa Wyse and Illustrator Kate Lewis. Reproduced by permission of Chronicle Books. All rights reserved.

Very interesting description of what promises to be a most fascinating read, and viewing, Mary Ann. Thanks so much, it sounds as if it’s really a visual and literary sharing of some superbly creative people’s dwelling spaces.