My journal is the seedbed for everything I write, the place where no judgment applies, not even my own . . Pat Schneider

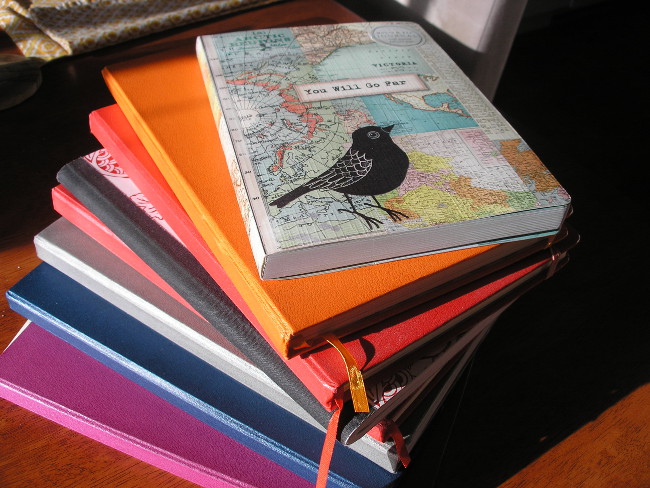

I’ve been thinking about and reading about journals and diaries lately. As I’ve been writing in journals almost daily for many years, I figure it’s time to weed them out. It’s unlikely I’ll publish my journals as Anais Nin did. She became known for her phrase about diary keeping as tasting life twice. (She may have done a bit of embellishing here and there.)

“A diary is an accounting,” Ian Brown writes in a Globe & Mail article (Saturday, January 17, 2015).

A notebook is different than a journal or diary, in my opinion, although Brown says his notebook can work as a diary. Each year he starts a new notebook that fits into his inside breast pocket. He says a notebook “is to record details that reach out as you pass, for reasons not readily apparent. A notebook is full of moments from days that have yet to become something.”

Brown quotes Joan Didion who wrote an essay called “On Keeping a Notebook.” She described keepers of private notebooks as “lonely and resistant rearrangers of things, anxious malcontents, children afflicted apparently at birth with some presentiment of loss.” All those rearranged things can make their way into other writing and due to the types of things and moments described, say as much about the observer as the observed.

Virginia Woolf didn’t intend her journals to be published but they’re fascinating to read as they describe her wandering journey as she figures out the writing of her novels. Hers could be called process journals which Louise de Salvo refers to in her book The Art of Slow Writing: Reflections on Time, Craft, and Creativity (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2014).

De Salvo uses a process journal to “plan a project, list books I want to read, list subjects I want to write about, capture insights about my work-in-progress, discuss my relationship to my work . . . sketch scenes, think about the work’s structure, puzzle through challenges I’m facing, and think through possible solutions.”

De Salvo uses a process journal to “plan a project, list books I want to read, list subjects I want to write about, capture insights about my work-in-progress, discuss my relationship to my work . . . sketch scenes, think about the work’s structure, puzzle through challenges I’m facing, and think through possible solutions.”

“Our process journals,” de Salvo writes, “are where we engage in the nonjudgmental, reflective witnessing of our work. Here, we work at defining ourselves as active, engaged, responsible, patient, writers.

Patricia Highsmith, author of Strangers on a Train and The Talented Mr. Ripley, kept two types of journals and left over 8,000 pages of them. Her biographer Joan Schenkar, describes them in The Talented Miss Highsmith: The Secret Life and Serious Art of Patricia Highsmith (St. Martin’s Press, 2009). “Cahiers” were for notes on writing and diaries were used for “life notes” and sexual encounters but sometimes she couldn’t keep the division separate. She’d make marginal notes in a “partitional format.” She “forged, fabricated and altered where necessary.”

The issue for me is what to do with these boxes of journals. I’d rather be rid of them than have someone else have to deal with them or read them. And there’s the matter of moving them all and storing them all when we move which is a possibility in the spring. My journals are full of daily accountings and complaining, disappointments, gratitude, the odd email printed out, news clippings, notes on the writing process and beginnings of poems, book reviews, blogs like this one and the recording of dreams. Described like that they sound too rich to destroy don’t they?

One summer I did look back to some journals written in the mid-nineties. It was a tedious process. I typed out some parts I thought I could use elsewhere especially if I write a memoir related to my writing journey. Just recently I was looking at what type of writing I was doing at certain times of my life. What I realized when I looked through the old journals is I remembered events in a different order than they actually occurred.

Reading an article in Poets & Writers magazine (September/October 2014) entitled “The Private Dwelling: Three Poets on Keeping (and Destroying) A Journal”, I could relate to Claudia Emerson who says she has “always been compelled to record things, finding some comfort in the act of writing something down, making tangible through that act what would otherwise be intangible, uneasy memory.”

Emerson writes in Moleskine journals recording the date each morning, noting the weather and writing entries “only on the right-hand pages of the book, saving the left side for lists and poetry notes. The back of the book is for lists of cool words, phrases, and notes from readings I attend.” She has been tempted to burn her journals as she thought they could all fall off the shelf in her study and land on her head. She has boxed up her journals and put them in the attic. “The journals remember things differently from the way I remember and that’s important and somewhat disturbing at the same time. I love the habit of writing and it seems to have its genesis in the journal, and that’s a present-tense value that I can’t give up, regardless of what it makes me feel later.”

Lisa Fay Coutley says her journal habits are a holdover from her teen years. She wrote in three-ring binders “as a way to organize chaos.” These days she says: “I still write to record and sort, and tend to be driven more by catharsis than by craft.” She has burned journals and found it to be “simple, thorough, and cleansing.” Sometimes she cuts the pages first, such as she did with her three-ring binders, and combined that with burning in a “nice, combined ritual.” She hasn’t regretted destroying her journals.

Anna Leahy writes in Moleskin notebooks too. She got back to keeping a journal “as a space for worrying” when her mother was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. She wanted her notebooks “to have a spine and continuity – and to be implicitly hopeful.” She threw her “spiral-bound notebooks full of college-age ramblings into a Dumpster in a parking lot.” She says: “Throwing out those journals was a way of telling myself to not be melodramatic, to move on, to grow up.”

Leahy says “Journal comes from words that imply a dailiness. Like a schedule of repeated, daily prayers.

Three other writers on Salt Spring Island have been meeting for seven years, journaling together and while they’re apart. Lynda Monk remembers writing in the middle of the night getting home from emergency child welfare situations when she was a social worker. Wendy Judith Cutler says her journal contained the drafts of her coming-out (as a lesbian) letter to her parents. Ahava Shira says her journals became “multifaceted: part psychological self-analysis, part creative muse, part travelogue, part relationship chronicle, part poetry handbook.” The three women just published a book called Writing Alone Together: Journalling in a Circle of Women for Creativity, Compassion and Connection (Butterfly Press, 2014.) The women describe their journaling process in the circle, offer prompts for your own writing and share their writing. There’s even a section near the end of the book on “Rereading Our Journals.”

Three other writers on Salt Spring Island have been meeting for seven years, journaling together and while they’re apart. Lynda Monk remembers writing in the middle of the night getting home from emergency child welfare situations when she was a social worker. Wendy Judith Cutler says her journal contained the drafts of her coming-out (as a lesbian) letter to her parents. Ahava Shira says her journals became “multifaceted: part psychological self-analysis, part creative muse, part travelogue, part relationship chronicle, part poetry handbook.” The three women just published a book called Writing Alone Together: Journalling in a Circle of Women for Creativity, Compassion and Connection (Butterfly Press, 2014.) The women describe their journaling process in the circle, offer prompts for your own writing and share their writing. There’s even a section near the end of the book on “Rereading Our Journals.”

So where am I now when it comes to my journals? I’ll take the advice of the women of Writing Alone Together when they say: “We can make the rereading safe and meaningful by coming back to the page with an attitude of self-acceptance and curiosity.”

I don’t think I’ll read the journals word for word. I’ll scan or even use a past journal as a divining tool. I can open the pages and see what advice from my past self, arises. I don’t want to get bogged down by the old words, really just want to make room for the new while honouring what was going on in the past. In the meantime, I’ll return, again and again, to my journal which, especially at night, is my little cabin of solitude with its white walls, its quiet welcome. There’s no phone, no email to answer, no interruptions at all. No need to be anywhere but here.

What a fascinating journey amongst many different journal writers and their words about why they write, when, what about and whether they keep their journals or let them go.

Thanks Mary Ann for a delicious read and for sharing your impressions from our book Writing Alone Together.

WIth gratitude and joy, for the journal and all its many facets,

Ahava

Hi Mary Ann, thank you for this great article and all the snippets of wisdom from various writers and journal keepers – it reminds me that while we often write for ourselves and on our own – we are always connected to a larger community of writers and journal writers who are also going to the page. Thanks also for your mention of our new book – for those who might be interested in it – they can learn more at http://writingalonetogether.com Next, I am ready to get on with my adoptee memoir – with your help through Writing Home. With gratitude, Lynda

Hi Mary Anne

Your blog made me reflect upon how I resolved the ‘what to do with my journals dilemma.’ I started journaling years ago after reading Julia Cameron’s ‘An Artist Way’.

I followed her suggestion of the three pages of writing daily and continued for several years. There was a time period that I began to re-read those entries and was amazed at the common themes that kept resurfacing. The insights became the inspirations for inspirational lines which I paired with pictures and music. This artistic endeavour was named Sacred Whispers.

The question what to do about this personal journaling came into the forefront each time I revised my will and thought about personal items.

This journalling was sacred to me . It tracked my very personal spiritual journey . I knew I couldn’t just throw this writing away unceremoniously .

Milner Gardens a very special place of beauty presented an opportunity to have my journals shredded while at the same time with a donation help support the gardens.

I watched my journals being shredded with some nostalgia, and a a prayer of gratitude for what they had revealed.

The energy of that writing had truly served its purpose. It was time to be released and to continue moving forward embracing new journalling.