Susan McCaslin and J. S. (John) Porter, poets and Merton scholars, offer a fresh and fully embodied study of Thomas Merton in their book Superabundantly Alive: Thomas Merton’s Dance with the Feminine (Wood Lake Publishing, 2018).

Merton, a Trappist monk who died in Bangkok, Thailand in 1968, was described as “superabundantly alive” by his friend Robert Lax. The book, Superabundantly Alive, with its insights and inquiry, was a joy to read.

Poems by both McCaslin and Porter open the book and are followed by McCaslin’s essay about her discovery of Merton’s work in 1968. She considers the late monk a spiritual mentor, “an imperfect pilgrim on the path to integral being. Increasingly, contemplation and action became his yin and yang, inseparable and complementary.”

McCaslin says: “Poetry seems to be Merton’s primary means of healing and transformation.” She studied Merton’s prose poem, “Hagia Sophia,” which is centered on the feminine divine and considers it his master work.

Porter, in his enlightening essay, “The Unbroken Alphabet of Thomas Merton,” explores the “key letters” in Merton’s alphabet such as J for journals and W for writer.

“Journals are a form of autobiography for Merton,” as Porter points out, “a way of keeping track of his days and preserving ideas and experiences that are important to him.” As for writing, Merton linked it to love and wrote: “For to write is to love: it is to inquire and to praise, or to confess, or to appeal.”

McCaslin and Porter have a dialogue entitled “The Divine and Embodied Feminine” in which McCaslin says: “The feminine for Merton is gentle, soft, fierce, strong, wild, and evolutionary. . . His God is masculine, feminine, liminal, androgynous, and mysterious beyond all our constructed categories.”

“Yes. Beautifully put.” Porter replies.

Another unique aspect of the book is “A Grotto of Sophia Ikons.” The poems are by McCaslin with graphic design by Afton Schindel and are in the form of ikons to “holy persons, people like all of us, flawed but moving toward a kind of radical wholeness.” They include Robert Lax, Joan Baez, Denise Levertov, Thich Nhat Hanh and Merton himself as St. Thomas Merton.

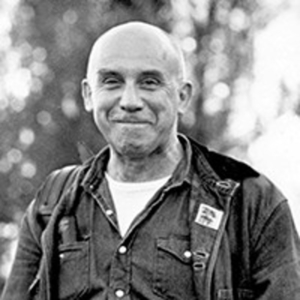

I love the photo McCaslin and Porter have chosen of Merton (by John Lyons), for their book. Rather than the photos of the contemplative monk, this one shows him ready to engage with others, in the world. He was such a fine example of doing both.

I love the photo McCaslin and Porter have chosen of Merton (by John Lyons), for their book. Rather than the photos of the contemplative monk, this one shows him ready to engage with others, in the world. He was such a fine example of doing both.

“Love and Solitude: A Cache of Love Letters for Tom and Margie” is a collection of letters by McCaslin to Thomas Merton and the nurse, Margie, he fell in love with at a Louisville hospital in the spring of 1966. It’s interesting to note that Merton composed his long poem, “Hagia Sophia,” where “Wisdom is Nurse, Mother, Sister, Beloved, the female Christ, the Ousia or very Being of Being” before meeting Margie.

The letters are a fascinating and innovative aspect of the book which contains various forms of exploration and discovery. That seems to be the perfect approach to writing about the life of someone described as “superabundantly alive. “

One of Merton’s poet friends was Denise Levertov and McCaslin’s essay “Pivoting Toward Peace” explores “the transformative poetry” of these two significant religious poets of the mid-to-late 20th century.

Having seen writing as her chosen form of “peaceful activism,” following retirement from teaching, McCaslin entered into the realm of sharing the fruit of her contemplation with others as Merton advised in Contemplation in a World of Action. She writes of the environmental activist campaign she and her husband Mark undertook to preserve a 25-acre mature rainforest not too far from their Fort Langley, British Columbia home in “Sophia Awakening Merton, the Trees, and Me.”

The Han Shan Poetry Project was named for an old hermit monk named Han Shan who is said to have lived on Cold Mountain during the Tang Dynasty, scribbling poems on rocks and suspending them from trees. McCaslin put the call out for poems and received them from other provinces in Canada well as from other countries. The poems were suspended from tree branches with colourful ribbons.

A portion of the forest was saved and then Mrs. Ann Blaauw stepped forward to purchase the land in its entirety as a legacy in honour of her late husband Thomas Blaauw. “Now renamed the Blaauw Eco Forest, the area is managed by Trinity Western University’s Environmental Studies Department.”

Merton’s journals, as McCaslin points, out “are punctuated with references to deer, birds, and trees. From the time of his earliest writing until his death, Merton expresses a sacramental vision of nature.”

The life and writing of Thomas Merton continue to ignite the imaginations of scholars of his work as well as newcomers to it. He was an “imperfect pilgrim” as McCaslin writes and perhaps that is why so many have embraced his work.

As McCaslin says in her opening essay, “The way [Merton] makes a gift of his own fragility gives us hope that each of us, with our own finitudes, flaws, and failures, may also touch holy ground. He is not removed from us, but a close friend.”

As McCaslin says in her opening essay, “The way [Merton] makes a gift of his own fragility gives us hope that each of us, with our own finitudes, flaws, and failures, may also touch holy ground. He is not removed from us, but a close friend.”

Susan McCaslin is a Canadian poet and Thomas Merton scholar who has published fourteen volumes of poetry. Her most recent volume of poetry is Painter, Poet, Mountain: After Cézanne (Quattro Books, 2016). Her recent memoir is Into the Mystic: My Years with Olga (Inanna, 2014)

J. S. Porter has been reading, thinking about, speaking about, and writing about Thomas Merton for 40 years. He has contributed to various journals on the subject of Merton. His books include The Thomas Merton Poems (Moonstone); Spirit Book Word: An Inquiry into Literature and Spirituality (Novalis); and Lightness and Soul: Musing on Eight Jewish Writers (Seraphim Editions). He lives in Hamilton, Ontario.

Thanks for the book review and the stories. Val would have loved this book. She was a huge fan of Merton. I love the title.

You’re welcome Gloria and thanks for reading it. I love the title too!

Merton was a life-changing catalyst for me. Thank you for this post and book information, and the inspiration to get back to writing.

Another luminous piece of writing, Mary Ann, weaving so many threads together… deep resonance with Merton, Sophia, love of nature, poetry, Denise Levertov (whose compiled writings I recently purchased), and the beautiful humanity of a soul willing to openly risk imperfection! Thank you.

Yes Andrea, so many threads to appreciate in Merton’s life and work. Risking imperfection: a wonderful motto! Thank you for your kind comments.

Dear Mary Ann,

I just discovered your review of John’s and my book on Thomas Merton, Superabundantly Alive, and think its the best and most comprehensive review we’ve received!! We both have nothing but gratitude. Your blog is a dream and a resource for writers and readers alike. Thanks for all you do to build community and realization in others of the transformative power of the arts. Having a book meet open and engaged readers is a fulfillment for the authors, and we very much feel our book has now been released to have its own secret life.

Superabundantly thankful,

Susan

Excellent Susan, I am pleased to hear that. I appreciate your comments as I’m glad to be a community builder and definitely a believer and promoter of the transformative power of the arts. Here’s to more people learning about Superabundantly Alive.I’m very happy to be helping to spread the word.

Superabundantly Enticing review, Mary Ann!