The poems are steeping; Jami Sieber’s CD Second Sight is playing – her voice and cello – and nothing is calling me to be anywhere else. The two cats are calm too. Even Squeaker who spent most of the summer outside is napping on the corner of my bed.

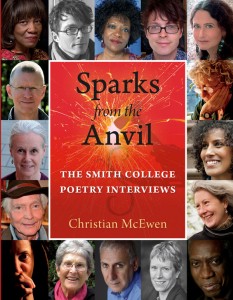

I can thank poet Nikkey Finney for that notion of steeping. She’s a poet who was interviewed by Christian McEwen for Sparks from the Anvil: The Smith College Poetry Interviews, a book I was reading the other morning.

I can thank poet Nikkey Finney for that notion of steeping. She’s a poet who was interviewed by Christian McEwen for Sparks from the Anvil: The Smith College Poetry Interviews, a book I was reading the other morning.

“So once I’ve released [the poem] and some commentary comes back, I feel like I’ve walked around it the five required times to look at it from all sides. I’ve looked at it in a thunderstorm, by candlelight, by fluorescent light, I stop, I put it away. I’ve looked at it and it steeps for a while, and I don’t read it for a long time. I come back to it, and when I’m reading it the next time, I can tell when it’s finished. Does it need something or not? And I can let it go,” Nikkey says in reply to Christian’s question: “So how to do you figure out when a piece of work is done?”

My poems are steeping – the ones that were released and came back with some commentary. I know there will be a time when they will insist on being looked at again. It isn’t right now. I’m experiencing a lovely silence, conducive to musing. This time is one of rest for me and a time of transition.

Jane Hirschfield in her interview in the same book says she praises silence rather frequently.

“I praise what happens within silence and the unsaid. And I praise not knowing, abiding in question rather than leaping to what may be a too-easy answer. I also often speak about transition in poetry. In fiction or playwriting, that is absolutely common. But in poetry workshops, it’s relatively rare. I asked my friends about this when I began teaching it, and no one had ever said a word to them about transitions in poetry. For a transition to happen, you need a gap, a little sabbath. I sometimes feel that all wisdom, all newness of insight and experience, lives in the hinges – of poems, of a life.”

Jane Hirschfield has written of gates and thresholds. That’s the first time I’ve seen the term “hinges” for a period of transition. I rather like the term as it relates to poems and to life: a place where “all newness of insight and experience” live.

I remember being at a David Whyte presentation at Royal Roads University in Victoria a few years ago. I was glad to meet David in person as I had been reading his books and listening to him on CD since 1997.

The day-long workshop was entitled “What to Remember When Waking.” He said: “A good sense of rest is going to put you in touch with the world again.” At the time (May, 2012), I was tired from all the outward-going energy.

David recites poems by heart and opened with the words of Wordsworth. Here are some of Wordsworth’s poem about walking one 19th century morning through the English Lake District where he had grown up:

. . . .

Ah! Need I say, dear Friend, that to the brim

My heart was full; I made no vows, but vows

Were then made for me: bond unknown to me

Was given, that I should be, else sinning greatly,

A dedicated Spirit. On I walk’d

In blessedness which even yet remains.

“The strategic mind can’t give you any happiness,” David said. He recited a poem which I believe is called “The Self-slaved” by Patrick Kavanagh: “A man must be free / From self-necessity . . “

Over lunch we were to ask ourselves: “What is the most beautiful question I can ask myself in my life right now? What would the courageous thing be to do?” My question to myself was: What if I did nothing?

“Deep rest is deeply transformative,” David said that day. “Rest isn’t a non-doing but an intentionality.”

I made notes but I’m quite sure I didn’t take a rest from the usual routine. We’re quick to take action, come up with to-do lists, market our wares and services but what if we and the work we do is best served by taking a rest.

I may not have taken a rest at the time but I am now as prescribed by an orthopedic surgeon (to follow radiation treatments and before surgery.)

This time is not without its challenges. I can’t help but think what’s next? As much as I enjoy solitude and some independence, I also like to be part of a community in which I see people every day. What will that look like for me in the future?

I am making the space for something else to come in.

David Whyte’s latest book is called Consolations: The Solace, Nourishment and Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words (Many Rivers Press, 2015). “Rest” is one of the words he writes about.

David Whyte’s latest book is called Consolations: The Solace, Nourishment and Underlying Meaning of Everyday Words (Many Rivers Press, 2015). “Rest” is one of the words he writes about.

“Rest is the conversation between what we love to do and how we love to be,” he writes.

“We are rested when we let things alone and let ourselves alone, to do what we do best, breathe as the body intended us to breathe, to walk as we were meant to walk, to live with the rhythm of a house and a home, giving and taking through cooking and cleaning. When we give and take in an easy foundational way we are closest to the authentic self, and closest to that self when we are most rested.”

He offers five states of rest:

“In the first state of rest is the sense of stopping, of giving up on what we have been doing or how we have been being. In the second, is the sense of slowly coming home, the physical journey into the body’s un-coerced and un-bullied self, as if trying to remember the way or even the destination itself. In the third state is a sense of healing and self-forgiveness and of arrival. In the fourth state, deep in the primal exchange of the breath, is the give and the take, the blessing and the being blessed and the ability to delight in both. The fifth stage is a sense of absolute readiness and presence, a delight in and an anticipation of the world and all its forms; a sense of being the meeting itself between inner and outer, and that receiving and responding occur in one spontaneous movement.”

He ends his description by writing: “In rest we re-establish the goals that make us more generous, more courageous, more of an invitation, someone we want to remember, and someone others would want to remember too.”

And so this time of rest is like a visit to a healing well, while staying at home where one can be in touch with shelter and the horizon at the same time.

David Whyte’s final poem at “What to Remember When Waking” was “Tobar Phadraic” (the Well of Patrick, a healing well people have been going to in Ireland for 5000 years):

Turn sideways into the light as they say

the old ones did and disappear into the originality

of it all. Be impatient with explanations

and discipline the mind not to begin

questions it cannot answer. Walk the green road

above the bay and the low glinting fields

toward the evening sun . . .

I love the quiet reflection and teaching that is coming from you quite naturally, without force or hectic spirit. I love the gems you are sharing, life in the hinges.

On a fun note, there is (I think) a typo, a “to-to” list where I expected a “to-do” list; and then all sorts of other meanings tumbled in: not just a “to-to” list but a “too-too” list and then “do-do” and, well, that’s enough. A lot of our “to-do”s are enemies of the deeper place where we dare to encounter ourselves, where we are worthy without any doing at all, a place of rest, restoration and release, a quiet well from which we draw our deepest strength and authenticity.

Thanks so much for continuing to share your wisdom and your healing journey.

Much love.

Thanks Bill. I made the correction to “to-do” list. I think you’re right. I probably meant “too-too” list.

The first word that came to mind when I came to the end of this post is EXQUISITE! Then a big YES! You have woven together so many colourful word threads filled with wisdom and deep knowing. A beautiful tapestry of poetry and prose that speaks directly to the heart has been created. As you draw on the writing of others you also expand the truth and brillance of your own creative presence. How wonderful for you to be resting right now and making way for what is to follow. Brava my friend! Brava

Thank you my friend.

a gentle teaching. thank you.

Thank you Mary Ann for the reminders from your own voice and those of David Whyte and Jane HIrshfield, to rest and surrender to silence. I agree with Beth. Brava.