Recently I found some haiku I had written when I still lived in Guelph, Ontario. I had been leading a writing circle called Journaling in the Garden at the Arboretum at the University of Guelph. The Japanese garden was the most inspiring of all. Writing haiku became one of our awareness practices.

the false Cyprus dances

with arms outstretched wearing

silk kimono sleeves

Here’s one inspired by Seeds from a Birch Tree by Clark Strand:

in seventeen beats

the poet captures moments

that celebrate life

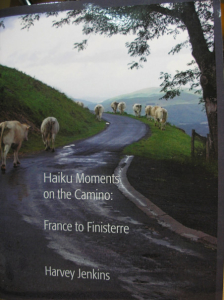

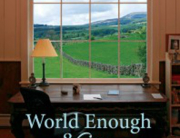

I sent off those first-written haiku, along with some others, to Harvey Jenkins who has been writing haiku for several years and received a Sakura Award from the Vancouver Cherry Blossom Festival in 2011, 2012 and 2013. Harvey and his wife Sharron have moved from Nanaimo to Winnipeg. While still living here, Harvey published his book: Haiku Moments on the Camino: France to Finisterre (Oliver Man Publishing, 2013). It became a non-fiction bestseller at McNally Robinson in Winnipeg following his reading there.

I sent off those first-written haiku, along with some others, to Harvey Jenkins who has been writing haiku for several years and received a Sakura Award from the Vancouver Cherry Blossom Festival in 2011, 2012 and 2013. Harvey and his wife Sharron have moved from Nanaimo to Winnipeg. While still living here, Harvey published his book: Haiku Moments on the Camino: France to Finisterre (Oliver Man Publishing, 2013). It became a non-fiction bestseller at McNally Robinson in Winnipeg following his reading there.

Among the guidelines Harvey sent back to me are these questions for writing haiku: Does your haiku name or suggest one of the seasons? Is your haiku about common, everyday events in nature or human life?

Harvey combined prose and haiku in his book, Haiku Moments on the Camino, which you can find in the Vancouver Island Regional Library or you can order a copy from McNally Robinson here.

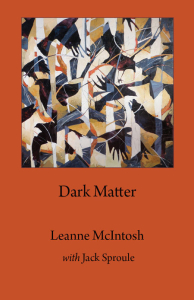

When I shared my haiku with Leanne McIntosh whose latest book is Dark Matter (Leaf Press, 2013), she told me: “Read the masters and trust the haiku will come if you pay attention.” I like that advice and think I’ll tell everyone that who is writing any form of poetry.  “Take the elements of haiku that appeal to you (simplicity, nature, one breath, image, juxtaposition of differences) and pay attention,” Leanne told me.

“Take the elements of haiku that appeal to you (simplicity, nature, one breath, image, juxtaposition of differences) and pay attention,” Leanne told me.

“Haiku is not a form poem, it is a way of being,” Leanne says and she quoted Basho: “Learn how to listen as things speak for themselves.”

Leanne has written haiku and is currently writing haibun, a combination of prose and haiku. The prose comes first followed by haiku which is not easy to do. As Leanne describes it: “I like the haiku to feel like the last drop of tea poised on the lip of the cup.” Exquisitely expressed, wouldn’t you say? (The photo of Leanne was taken by Chris Hancock Donaldson at the launch of chapbook anthologies by the Honeymoon Bay poets at the Globe in Nanaimo on July 16, 2014).

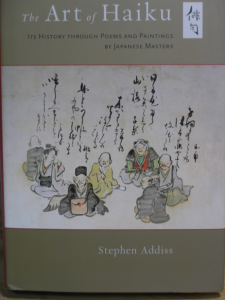

I’ve been reading Basho and other Haiku masters in a book called The Art of Haiku (Shambhala, 2012). Author Stephen Addiss says Matsuo Bascho (1644-94) “has been almost universally regarded as the greatest master of haiku.” He was born in the province of Iga, thirty miles south of Kyoto. In 1681, Basho was given a plantain (banana, basho) tree by a pupil for his new home. As Stephen Addiss writes: “He so identified with the tree that it became his most celebrated haiku name.”

The Art of Haiku also features colour plates of haiga paintings by Basho and other masters.

The Art of Haiku also features colour plates of haiga paintings by Basho and other masters.

Basho and Benedictine monk David Steindl-Rast are quoted in an article in the January 2014 issue of Shambhala Sun. In the article, “Poem of Silence,” Mary Rose O’Reilley writes that “Haiku’s subject is, in small letters, enlightenment – everyday mindfulness, a grateful record of daily grace.”

Brother David says, “The haiku is a scaffold of words; what is being constructed is a poem of silence; and when it is ready, the poet gives a little kick, as it were, to the scaffold. It tumbles, and silence alone stands.” I’ve been a fan of Brother David’s work since I read The Music of Silence: A Sacred Journey Through the Hours of the Day (Seastone, 1998, 20012).

Mary O’Reilly began a haiku practice as part of her spiritual practice, trying to stay present to the “outer world, rather than to my inner condition.” She does say in her article that she steadily fails at this. If they were “lame” she just remembered the words of poet William Stafford and lowered her standards. There’s so much more to write about haiku as there are many haiku poets in Nanaimo and vicinity. I’ll write about them in a follow-up blog. Here’s one of Basho’s famous haiku:

furu ike ya

kawadzu tobikomu

mizu no oto

The English translation is:

old pond

frog leaping

splash.

As Mary O’Reilly says, the English translation may leave us “on the shore of a big huh? But memorizie it, live with it, and Basho’s moment works its way into your spirit.”

I really enjoyed reading this. I know very little about Haiku. Your stories and poems have given have enriched my experience of poetry. Thank you!

I, too, know very little about Haiku, but your post inspired me to try one. It’s not nearly as creative as your comparison of moss to kimono sleeves – so inspired – but it was fun to give it a try.

random branches dance

leaves rustle as the breeze

sighs its soul-filling content

The sound of the breeze on deciduous leaves was one thing that I missed about the east when living in the west! I love the sound.

Haiku is a wonderful practice that gets us in touch with the miracle of the “every-day” things. A gratitude practice.

Thanks so much Mary Ann!

[…] I wrote an earlier blog called Ephiphanies of a Landscape, also about haiku, featuring Terry Ann Carter. You can read it here. Another earlier blog, Haiku Moments, features Harvey Jenkins’ book Haiku Moments on the Camino. You can read that blog here. […]